|

Does it actually matter how you dress when you go to work? The BMJ recently published an open access article covering this exact issue. Although in many ways limited, this study offered some key insights regarding how our dress attire in different settings could potentially impact patient perceptions.

The study, conducted at 10 academic hospitals in the United States, surveyed 6280 individuals with a response rate of approximately 65% resulting in 4062 patients responding. 53% of patients said that the dress of their physician was important and 36% said it influenced the satisfaction of their care. Only 15% did not find dress important and only 23% did not think it influenced care.

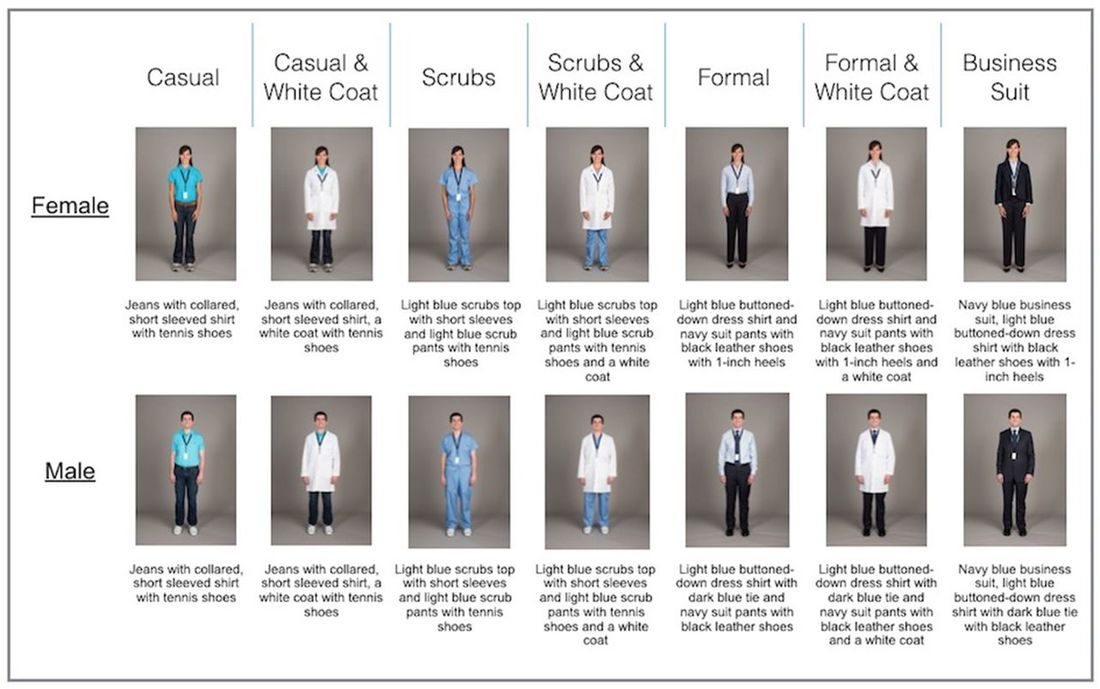

Those who responded to the survey were primarily over the age of 55 (64%), male (65%), having at least some college education (70%), white (71%), seen at least three doctors in the past year (80%) with 38% seeing 6 or more in the past year, and were primarily from the Midwest (55%) or South (28%). In general, this was an older, white, male, higher educated group of individuals who frequently access the healthcare system and are from traditionally conservative parts of the country. These patients were approached by research staff (who worked "normal business hours") as a convenience sample of those in waiting rooms and those in hospital rooms. Patients were given 5-10 minutes to respond to the survey in private with no identifying information collected. As shown below, patients were shown a series of pictures that were randomized of individuals dressed in different styles of clothing: casual wear, casual with white coat, scrubs, scrubs with white coat, formal attire, formal with white coat, and a business suit. There were both male and female pictures. These were professionally done pictures of two young, slender, white individuals.

Although overall formal attire with a white coat was the highest rated, the difference is mild compared to the bulk of the other outfits safe the casual dress. Formal attire with a white coat had a mean composite score of 8.1 (SD 1.8) with the next closest being scrubs with a white coat having a composite score of 7.6 (SD 1.9). Although statistically this had a significant difference, most composite scores were around 7 with casual dress having 6.2 as its composite score.

The more interesting breakdown is the preferred attire by setting. In a primary care setting, formal dress with a white coat was far preferred (44%). Scrubs, with (34%) or without (40%) a white coat was far preferred at 74% in the emergency department. While in the hospital, whether it was with scrubs (29%) or formal attire (39%) patients wanted a white coat (68%). Scrubs again were key in surgical settings (65%) whether with (23%) or without (42%) a white coat. When asked overall, scrubs (26%) or formal attire (44%) with a white coat at 70% was key. This sounds great and clear cut at a superficial level, but we need to consider different factors that may influence the results. Although this was a well done study methodologically that included well done photographs, the pictures were only of slender, young, white individuals. It would be interesting to see if factors such as body shape, age, and skin color impact the dress attire people would prefer. Obviously, this would introduce other potential biases but it is worth noting this potential limitation. Another important limitation is regarding the respondents themselves. We are starting with an already conservative sounding group of individuals (older, white, male, higher educated, and from traditional conservative regions) providing the responses. The paper even reflects that those respondents over 65 years of age preferred formal attire with white coats than younger patients (44% versus 36%). This again appears to be more important in the southern part of the United States. Also on the topic of the United States, this may not be a very generalizable study. In the United States, there are not the restrictions held in other parts of the world (such as with the NHS) that requires "bare below the elbow" (BBE) which in strict form means nothing can be allowed distal to the elbows including clothing, watches, and rings. Short sleeve clothing would exclude most white coats and formal attire. There is strong symbolism that the United States still holds for white coats. It represents science to help differentiate them from the barber surgeons at the time. White coats are still a major part of medical school training with special ceremonies in place. This has transferred over to patients who see the connection since it was first promoted. Given how ingrained the white coat is in the United States, the white coat may be important here but less so internationally. There are traditional biases to consider such as the possibly that someone could perform the survey multiple times if they returned. Also, demographics were not obtained for those who refused to complete the survey. Reported impressions from the survey may not reflect actual preferences but current feelings toward their care. Similarly, there is the potential for the Hawthorne Effect where patients may have answered questions in a manner they believe would be satisfying to the researchers. Although Census data demonstrated that patients were for the most part equal to the study population, the higher white population and lower than anticipated Hispanic population (5% versus estimated by the Census as 16%) could also play a role. Finally, the way the survey was constructed (such as the Likert scales) may not accurately reflect what the respondents were feeling. In all, this was not a bad study. However, we must recognize the limitations of the study when looking at the findings. There are obvious potential biases, but this can help give us a way forward. In the United States, formal attire with a white coat seems to matter more in primary care settings, scrubs are preferred in the emergency department and surgical settings, and a white coat matters in the hospital settings. Overall, a white coat seems preferred but this may not be as important in other parts of the world. However, this could be because of the population that was studied. Let us know what you think by giving us feedback here in the comments section or contacting us on Twitter or Facebook. Remember to look us up on Libsyn and on iTunes. If you have any questions you can also comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed