|

We love EB Medicine specials and we hope you do, too! This time we are talking about a subject that many forget about: pediatric stroke. While it is far less common than what we see in the adult population, it carries a high morbidity and mortality rate. In November, EB Medicine went into detail about this particular topic and we think it was a fantastic review. Let's get started!

For access to this article make sure to click this link. If you do not have a subscription yet with EB Medicine you will not be able to get the associated CME. However, check out the end of our show notes to learn how you can get access and at a great discount.

We have discussed the topic some in the past with Lawrence Berdan back in Podcast #122 when we also spoke about traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). His first-hand experience in the subjects was enlightening and it is worth revisiting if you have not heard it before. Annually, 1-2 per 100,000 children are affected by strokes. and carries with it a mortality rate of up to 10% in arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) and 25% for hemorrhagic stroke. Despite potential neuroplasticity (the ability of the brain to change continuously throughout an individual's life), two thirds of children will have persistent neurological deficits. Pediatric strokes often are more difficult to initially identify and diagnose compared to adult cases. The median time of stroke in one urban center was 22.7 hours from symptom onset to diagnosis and 12.7 hours from hospital presentation to diagnosis. On initial assessment, the diagnosis was only suspected in 38% of the cases. For categorization, ischemic strokes encompass both AIS and cerebral sinus venous thrombosis (CSVT). AIS is an acute neurological deficit with an acute infarct in a corresponding arterial territory on brain imaging. The most common causes are as follows:

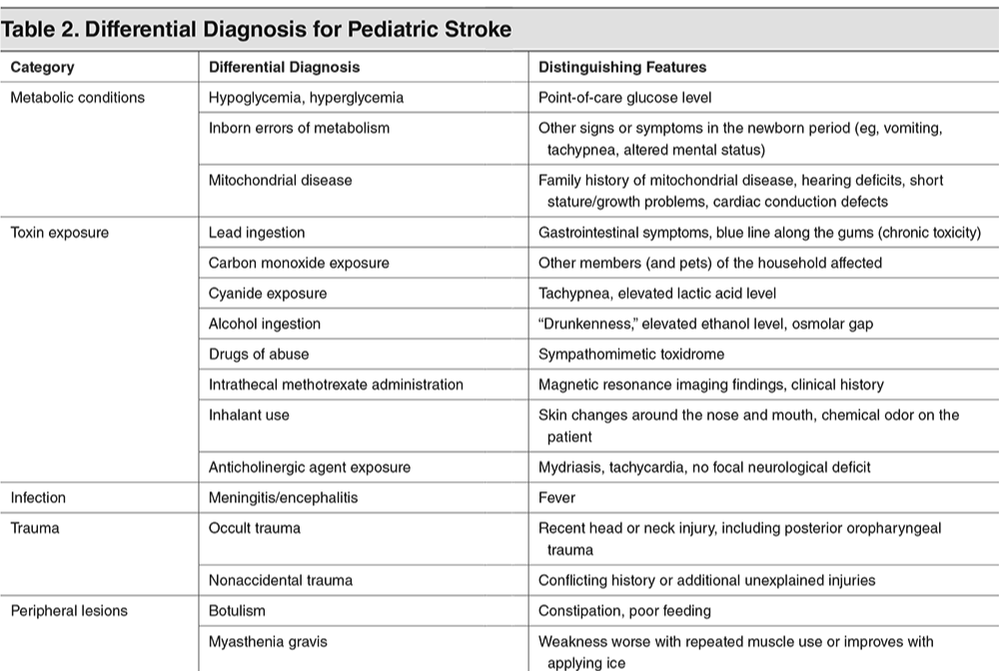

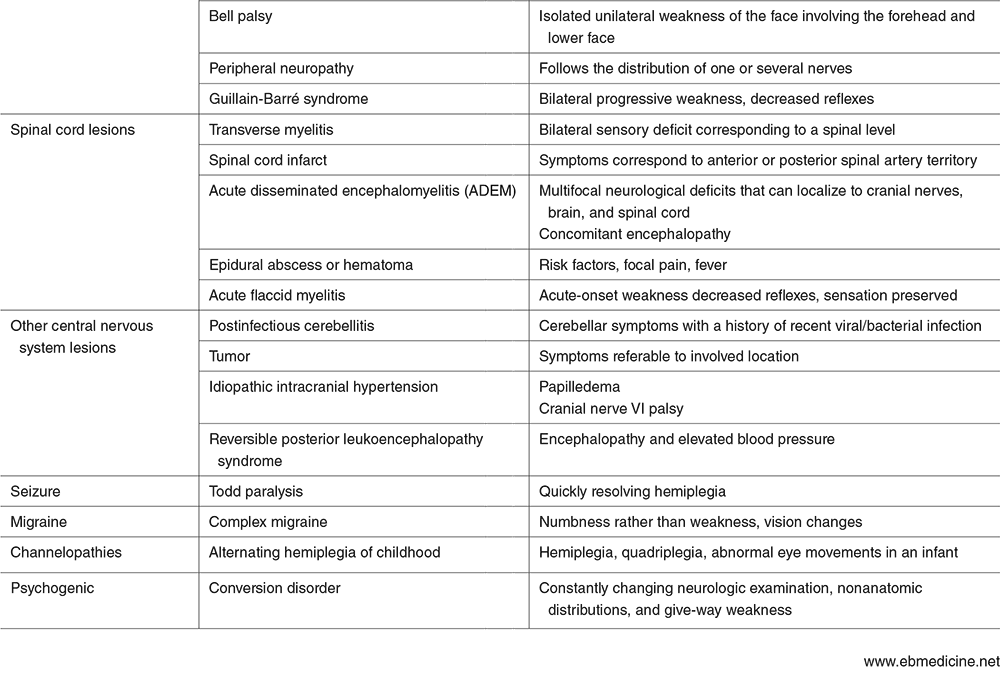

CSVT is the state of abnormal clot formation in the deep and dural venous sinuses of the brain. This can lead to impaired arterial inflow and ischemia. It may not follow an arterial pattern. CSVT may present with focal neurological deficits and signs of increased intracranial pressure (ICP). The treatment is to the underlying cause (such as infection or dehydration) and anticoagulation (even if hemorrhage is present). Hemorrhagic stroke is defined as any nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or intraventricular hemorrhage (excluding those related to prematurity). While most strokes in adults are ischemic, children have an equal incidence of ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Arteriovenous (AV) malformations are the most common cause. Bleeding disorders may also cause pediatric hemorrhagic stroke with thrombocytopenia being the most common hematologic cause of intraparenchymal hemorrhage. The differential diagnosis is extensive, but the most common stroke mimics are migraines, seizures, Bell's palsy, conversion disorder, and syncope. For the most part these are more benign, there are potential emergencies that can mimic stroke such as meningitis, encephalitis, brain tumors, and TBIs.

Differentiating strokes from migraines can be challenging in both adults and children. Migraines are more frequently associated with visual symptoms and vomiting. The neurological deficit in a complex migraine is most commonly associated with focal numbness. Neurologic symptoms of migraine commonly resolve within 30 minutes. AIS presents with sudden-onset focal weakness (less commonly with numbness), speech or language changes, ataxia, and/or seizures. Infants are more likely to have nonfocal signs such as altered mental status or seizures.

A solid history can help identify and distinguish strokes from its many mimics. The history should be focused on the time of onset, stroke risk factors, and elements that can help narrow the differential (such as fever, trauma, and family history). Risk factors for AIS include sickle cell disease, congenital heart disease, and prothrombotic conditions. Recent head, neck, or respiratory infections within the preceding three days can be another risk factor. Risk factors for hemorrhagic stroke include antithrombotic medication use, bleeding disorders, thrombocytopenia, cancer, and history of intracranial hemorrhage. Sickle cell disease can also increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. In regards to the physical examination, the first step is to assess airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) as always. This is followed closely by a neurological exam. For the critically ill patient, try to establish a baseline exam prior to intubation. This should include evaluating movement of all four extremities and level of responsiveness. The NIHSS has been adapted for children aged 2-17 years called the PedNIHSS which accounts for the developmental level of the child. Another step that should be considered is assessing for toxidromes as this is a frequent mimic. Testing should be focused on stroke mimics with a very important one being blood glucose. Other lab studies include CBC, CMP, PT/INR, PTT, toxicology screen, and potentially a pregnancy test when appropriate. An EKG should also be obtained. Initial imaging, especially in areas with limited MRI access, should be CT. This will be focused on ruling out hemorrhage first. Vascular imaging should be obtained when ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke is identified or highly suspected. Initial treatment should be stabilization including addressing the ABCs. Correcting hypoxemia, hypoglycemia, dehydration, anemia, and fever should also be performed. Anticonvulsant medications are not done empirically in the absence of seizures. In AIS, antiplatelet medications such as aspirin and anticoagulants such as heparin (or LMWH) are used. In CSVT, unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) are recommended in addition to treating the underlying cause. Thrombolytics are not the standard of care but may be considered in specific situations (in coordination with pediatric neurology). Mechanical thrombectomy is another option in AIS and has been performed in children as young as 2 years of age. Sickle cell disease significantly increases the risk of stroke compared to other children. The incidence is as high as 285 cases per 100,000 children per year. When treating children with sickle cell disease, the treatment has some variation. Aspirin is given but the primary goal is to decrease the amount of hemoglobin S. Transfusion of red blood cells to a total hemoglobin of 10 to 11 g/dL is one target. Another target is a reduction of hemoglobin S to <30% which can also be obtained with exchange transfusion. Hemorrhagic strokes are managed by preventing further bleeding. Also, hypotension should be addressed while avoiding hypertension. Hypoxemia and hypoglycemia should also be treated. Intracranial pressure should be kept from rising. Elevating the head of the bed to 30 degrees and keep the patient calm and/or sedated can be utilized. Surgical craniotomy is an option when decompression is needed. It is worth noting that management remains somewhat controversial. Outside of sickle cell disease, no randomized controlled trials exist in the management. However, early identification is key for treating these patients appropriately. Did you enjoy the content? Would you like to learn more about EB Medicine? Right now, you can get $50 OR MORE off a subscription with EB Medicine. Just click on this link and go to their website. Let us know what you think by giving us feedback here in the comments section or contacting us on Twitter or Facebook. Remember to look us up on Libsyn and on iTunes. If you have any questions you can also comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed