|

Blunt trauma in the pediatric patient is fairly common. Blunt trauma to the abdomen though is less common and provides some unique challenges. The patient's developmental stage, limitations in verbal and language skills, lack of prehospital information, and the potential for an unreliable exam creates a situation that can create additional stress for both the family and those taking care of the patient. We will break down a recent EB Medicine article and cover some of the key aspects that will help you provide better care to these patients.

For access to this article make sure to click this link. If you do not have a subscription yet with EB Medicine you will not be able to get the associated CME. However, check out the end of our show notes to learn how you can get access and at a great discount.

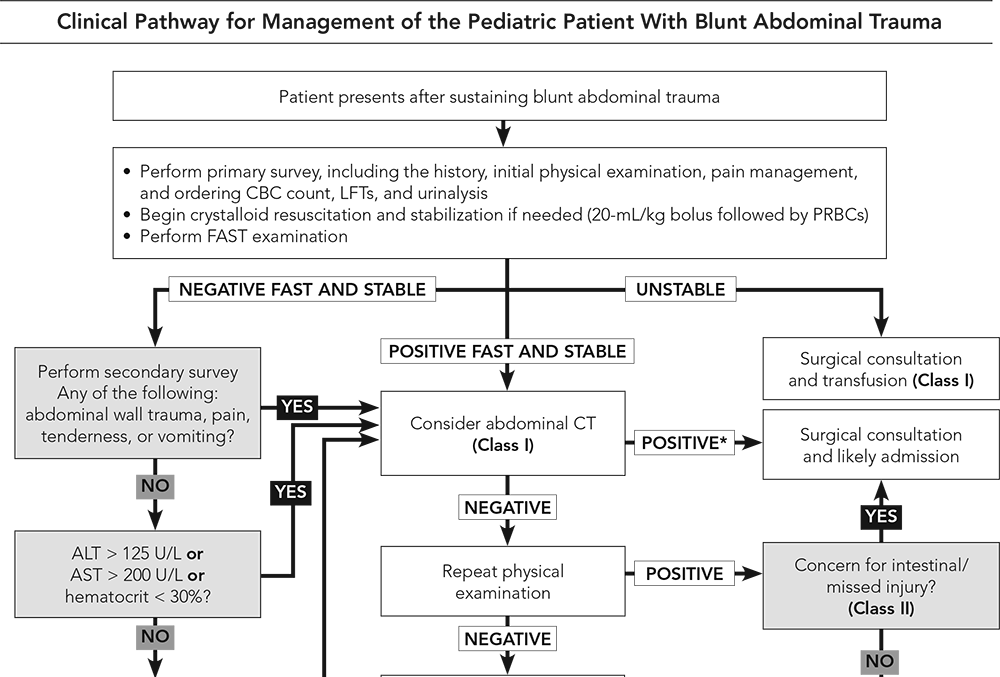

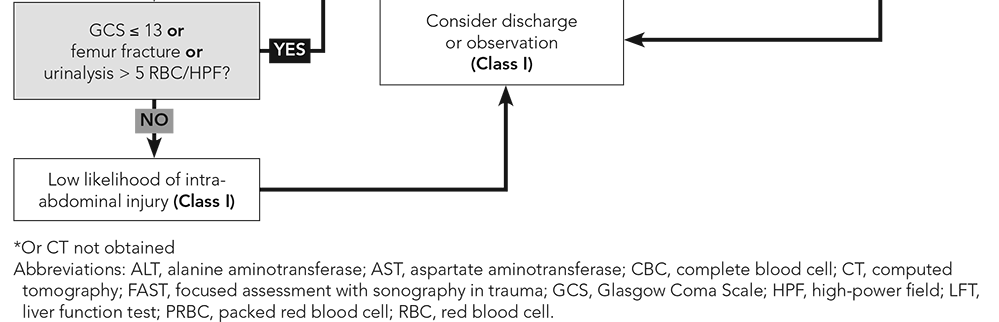

Introduction Unfortunately, blunt abdominal trauma is the third most common cause of pediatric deaths from trauma (head and thoracic being more common), but it is the most common unrecognized cause of death. Motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) are the most common cause of death in children 5-18 years of age. The spleen and liver are the most commonly injured abdominal organs but the kidney, small bowel, and pancreas can also frequently be injured. Pathophysiology Children can present some very important challenges based on their anatomy and physiology. The abdominal organs are relatively larger in children than adults. Their poorly developed abdominal muscles, less intra-abdominal fat, and a compliant rib cage increase their risk for more significant injuries compared to their adult counterparts. Additionally, crying is very common both from pain or fear. Swallowing air when crying can lead to gastric distention versus the distention we can be concerned about in trauma. In addition, crying can elevate heart rate, but tachycardia is also a common early indicator for blood loss. We see hypotension later in children and other signs of blood loss can be seen later than in adults. Children can become hypothermic more easily than adults which can worsen shock. Given their smaller body mass, children are more likely to suffer multiple injuries given that force is applied to a small body surface area. Common Mechanisms Head injuries are the most common cause of death in MVCs, but the pattern of injury from MVCs varies by the type of restrained used, seating position, and type of accident. Appropriate restraints can help decrease abdominal injuries in children. Inappropriate restraint with lap-only belts or lap-and-shoulder belts can lead to injuries from the seatbelt including hip and abdominal contusions, pelvic fractures, lumbar spine injuries, and intra-abdominal injuries to both solid organs and hollow viscera. A positive seatbelt sign is concerning for intra-abdominal injury with higher rates of gastrointestinal and pancreatic injuries. However, some limited evidence has demonstrated that those with a positive seatbelt sign but without abdominal tenderness did not have an intra-abdominal injury. Side impacts are a more common cause for abdominal injuries compared to frontal impacts. Children hit as a pedestrian by a motor vehicle is dangerous with injury patterns depending on vehicle speed, angle of impact, center of gravity of the pedestrian, body part contacted by the vehicle, part of the vehicle impacted, and vehicle design. There has been a trend to an increase in both incidence and severity for abdominal injuries related to bicycle accidents. Handlebar injuries are often underappreciated in early presentations but can have significant underlying pathology. Direct impact with a handlebar requires a high index of suspicion and can event be delayed by over a day. Sports injuries are a less common cause of abdominal injury but the spleen is most commonly injured, but other commonly injured organs include the kidneys and liver. American football, rugby, soccer, hockey, cricket, snowboarding, and baseball are some of the riskier sports for abdominal injuries. Falls are the most common cause of nonfatal injuries in children and approximately 4% had an intra-abdominal injury and are more common with higher falls (15 feet or higher). A worthy note based on one meta-analysis found that no small bowel perforations were caused by falls down stairs and such injuries with that type of trauma should be suspicious for non-accidental trauma (NAT). Speaking of NAT, these patients tend to be younger, more severely injured, and more often require more serious interventions such as surgery and intensive care. Hollow-viscus injuries tend to be more common as well as a combination of hollow-viscus and solid-organ injury. There is also often a delay in seeking care. Assessment The primary survey should be like any other trauma patient with the focus on addressing immediate life or limb-threatening injuries as well as preventing neurological compromise. In addition, point of care ultrasound (POCUS) should be utilized when available to perform key exams such as the Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (eFAST) exam. A focused history may be difficult to obtain due to the patient's age, clinical condition, availability of and knowledge of the situation by caregivers, limitations in their verbal skills, and extrinsic motivations (such as wanting to avoid getting in trouble). Obtaining information such as where and how the injury occurred are vital just as described above. Important past medical history such as bleeding disorders, anemia, medications, and allergies need to be known. The surgical history such as if there were previous abdominal injuries are important. Knowing the child's baseline and having a reliable caregiver to provide this information is also important to evaluate for neurologic injury. It should be known that children with a developmental delay or autism may be more difficult to assess. The secondary survey is a head-to-toe exam to look for those injuries that are not an immediate threat to life, limb, or neurological. Rectal exams are no longer recommended to be performed routinely given its poor sensitivity. However, the genitals and perineum should still be evaluated especially before catheter placement. A negative examination and the absence of comorbid injuries does not necessarily rule out an intra-abdominal injury. Abdominal tenderness, ecchymosis, and abrasions are concerning for intra-abdominal injury. A low systolic blood pressure, decreased level of consciousness, and signs of peritoneal irritation are all concerning and carry a higher risk of intra-abdominal injury. Diagnostics While the routine use of trauma panels is no longer recommended, two reasons to perform laboratory testing are for the potentially unstable patient and to screen a stable child for a possible intra-abdominal injury. The most useful tests are a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, and urinalysis. Elevation of the AST, ALT, or hematuria in the presence of abdominal tenderness should be taken seriously as these patients are at higher risk for a clinically important abdominal injury. Amylase and lipase, however, have not been proven to be helpful. Given the concerns of lifetime risk of fatal malignancy, computed tomography (CT) should be avoided whenever possible and requires a more thoughtful approach than the general method of evaluation for adult trauma patients. The eFAST exam is widely used in adult trauma, but in the pediatric population this has been more controversial. However, it is very beneficial in that it is noninvasive and repeatable. While a negative eFAST exam is not as helpful, a positive exam can significantly impact management. CT with intravenous (IV) contrast has become the gold standard for abdominal imaging in trauma. Oral contrast may still be indicated in specific situations such as suspected pancreatic or hollow-viscus injuries, but are less widely used. Even a repeat CT scan is unlikely to confidently exclude a bowel injury including when symptoms have been worsening on exam. Children seen at community hospitals should avoid CT whenever possible since these scans are often repeated at trauma centers. Management This topic is quite complex, but EB Medicine excelled in covering this area and it is worth reviewing it directly in their article. However, we will still review some of the key pearls. Initial stabilization should be the goal including achieving hemodynamic stability. Generally, avoid the use of crystalloid fluids and go straight to blood products to achieve this stability whenever possible. 10 to 20 mL/kg of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) should be given. Crystalloid fluids can be used if blood products are not readily available. The ultimate goal should be achieving hemodynamic stability and appropriate transfer. An important and often forgotten component of early management is pain control. For an overall approach, refer to the clinical pathway below by EB Medicine.

Did you enjoy the content? Would you like to learn more about EB Medicine? Right now, you can get $50 OR MORE off a subscription with EB Medicine. Just click on this link and go to their website.

Let us know what you think by giving us feedback here in the comments section or contacting us on Twitter or Facebook. Remember to look us up on Libsyn and on iTunes. If you have any questions you can also comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed