|

Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening condition. It needs to be identified quickly and treated appropriately to save a patient's life. Today marks our first ever "Patient and Provider" podcast. This means that although the podcast itself is still meant to provide more of the basics, the blog will also be helping educate patients in the relevant condition. Check both the blog and the podcast for all the details.

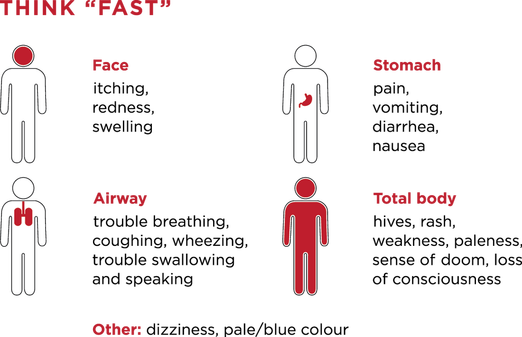

As the "Think Fast" graphic from this site above demonstrates, there are many symptoms to watch for to help diagnose anaphylaxis. Remember from the beginning the ABCs: airway, breathing, and circulation. In these patients, keep a close eye on the airway as they may need intubation should there be significant airway swelling that cannot be readily controlled. Mucosal or airway swelling can be defined as swelling to the lips, tongue, or uvula. Check breathing by looking for respiratory compromise. Common findings are difficulty breathing, wheezing/bronchospasm, stridor, or hypoxia. After assessing airway and breathing, check for cardiovascular collapse. This would be seen as reduced blood pressure or other concerning symptoms such as collapse, syncope, or incontinence.

Most commonly there are skin changes and usually found quickly. This often present as generalized hives, itching, or flushed skin. Something less commonly noted but also important are gastrointestinal symptoms. Think about cramping abdominal pain and vomiting. In all, there are many ways to define anaphylaxis but there are three main criteria: 1. The acute onset of a reaction within minutes or hours involving skin and/or mucosa paired with either respiratory compromise or cardiovascular collapse. 2. Use the second criteria set for symptom development from exposure to a likely allergen. Any of the following two categories are needed for diagnosis: involvement of skin and/or mucosa, respiratory compromise, cardiovascular collapse, or gastrointestinal symptoms. 3. If a patient has a reduced blood pressure after exposure to a known allergy within minutes or hours, this meets the third criterion. Hypotension is usually defined as a systolic pressure of less than 90 mm/Hg or a 30% decrease from baseline. In children, blood pressure for those less than 10 years old is defined differently. At less than a year old it is a blood pressure of 70 mm/Hg. Between years 1 and 10, it is 70 with the age times two. A quick example would be that for a 5 year old child, the systolic pressure concerning for hypotension would be 80 mm/Hg.

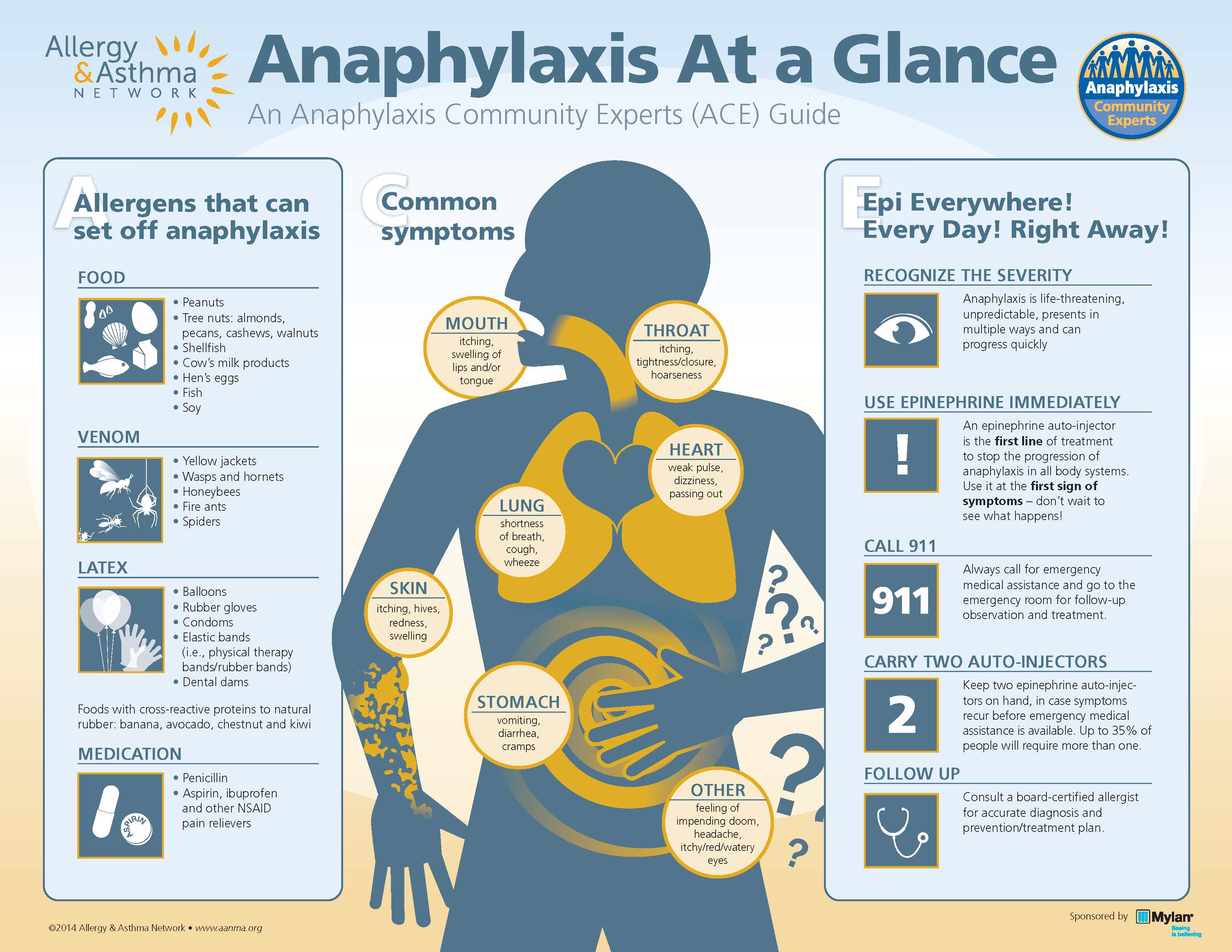

It is worth mentioning for a brief moment some of the causes for anaphylaxis like the ones listed in the graphic above from this site. Although most people will not recall a specific cause, once the patient or someone else has a chance try to narrow it done. However, remember that these causes are often not identified. Make sure to ask about food, possible bites/stings, medications, or products including latex. The main thing to do is treat anaphylaxis quickly but if identifying the underlying cause is possible this could allow for faster treatment.

The first and most important treatment is epinephrine. There are a number of articles such as this one that help cover the importance of epinephrine. Most commonly, epinephrine is given in the muscle. Part of the reason is that administration should not be delayed for IV access. There has been an association of delayed epinephrine being associated with death. If needed, repeat doses of epinephrine are given either in the muscle or by IV. Given its life-saving importance, commercial auto-injectors are available to the product with the most common being EpiPen. However, the cost has been on the rise recently which has limited access to some patients. This is a separate debate though and one filled with controversy. As a provider, make sure that you prescribe an epinephrine auto-injector prior to discharge. Remind patients too that the two auto-injectors should be kept together (more on that in a bit). Remember, there are no absolute contraindications for epinephrine in anaphylaxis. During the same timeframe of giving epinephrine, there are other initial measures that are important. Removal of what caused the allergic reaction is often forgotten. For suspected food exposure, have the patient rinse their mouth and possibly brush their teeth. Antigen removal helps reduce the risk of continued reaction. For medications this would mean stopping the medication once recognized. Another important point is to call for help, especially if not in a place where definitive care can be given. Fluid resuscitation and supplemental oxygen can also be given. There are a number of other medications that can be used in addition to epinephrine in anaphylaxis. Patients on beta-blockers may be resistant to treatment with epinephrine and can develop hypotension that glucagon could help correct this issue, but the evidence is limited (here is one article). If epinephrine is not enough for the respiratory issues of wheezing and bronchospasm, consider using bronchodilators such as albuterol. However, there is limited evidence (one example) and does not treat upper airway obstruction or laryngeal edema. Antihistamines such as diphenhydramine and ranitidine should be considered but there appears to be no direct evidence in their use with treatment in anaphylaxis. Most evidence seems to relate from patients who developed allergic reactions such as hives. However, they can be helpful in certain situations and are often administered. Steroids can be beneficial as well and often given. Usually steroids are given early in anaphylaxis to help reduce the risk of relapse but there is some debate based on current evidence if it is actually effective. With all of these medications, you may ask yourself about how to do the dosing. Traditionally with epinephrine especially in the auto-injector form it is 0.3mg in the muscle (IM). For those who are greater than 50kg, a dose of 0.5mg can be used. Additional doses can be given IM or through an IV. With albuterol, usually 2.5mg is given for bronchospasm if epinephrine is not sufficient. In regards to antihistamines, IV doses of diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and ranitidine (Zantac) are given as dosing up to 50mg. Methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol) can be given up to 125mg IV or IM. If you are treating a pediatric patient in anaphylaxis, the epinephrine dosing is 0.01 mg/kg up to the max of 0.5mg per dose. When it comes to the antihistamines specified (both H1 and H2) and methylprednisolone the dosing is relatively straightforward. For each you give 1mg/kg up to their maximum dosing. There are even more treatments for anaphylaxis especially when the initial medications do not work. However, this is complex and best reserved for its own special discussion. One concern after the initial management is if there will be a second reaction. This is known as biphasic anaphylaxis and is uncommon. A relatively recent study found that clinically important biphasic reactions are rare and so are the fatalities. In that study there were reactions ranging from 10 minutes to six days after the initial reaction. Evidence now seems to show that routine monitoring is not beneficial given the rarity. Did you like this new approach to a podcast and blog? If you are a patient, remember to look at the "For the Public" section for more basic details. Feedback, as always, is appreciated. Remember to look us up on Libsyn, share on Facebook, retweet on Twitter, and rate on iTunes to help spread the word on TOTAL EM. If you have any questions you can comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed