|

We are finally back with another ATLS podcast. Mike Sharma and Chip Lange together discuss the complex but important subject of thoracic trauma. They break it down this time by addressing key aspects that come up during the primary and secondary assessments. This topic also broaches how to manage the traumatic circulatory arrest patient without a pulse.

ATLS emphasizes some key points and one is that most life-threatening thoracic injuries can be treated with airway control or decompression of the chest with a needle, finger, or tube.

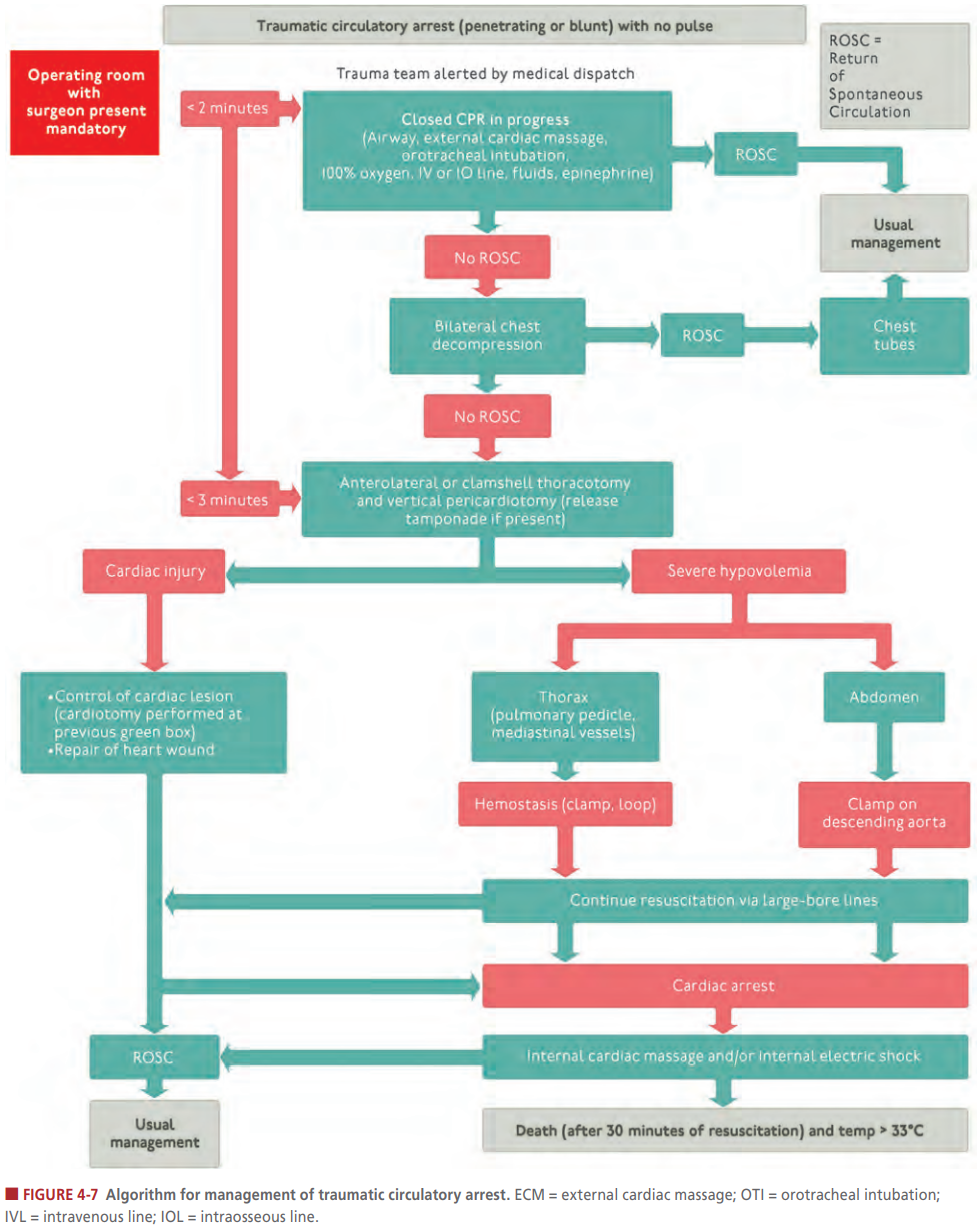

For example, airway problems include airway obstruction (fluids, edema, and even posterior clavicular dislocation) and tracheobronchial tree injury (pneumothorax not resolving with a chest tube). Breathing problems would include tension pneumothorax, open pneumothorax, and massive hemothorax. The circulatory problems include massive hemothorax, cardiac tamponade, and traumatic circulatory arrest. In the event of a pulseless traumatic circulatory arrest, ATLS with Figure 4-7 provides a nice algorithm to run through in these events.

As mentioned in the previous ATLS podcasts, point of care ultrasound (POCUS) can be very beneficial in identifying some of this pathology. Classically, it is taught to use a stethoscope to listen for some of the findings such as diminished breath sounds. However, in a busy and loud environment, this is rather difficult to do with a stethoscope. Fortunately, with POCUS you can avoid this issue. Ultrasound can help identify pathology such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, and pericardial effusion. Additionally, POCUS can help with guiding our procedures such as where to place a chest tube and for needle guidance during pericardiocentesis.

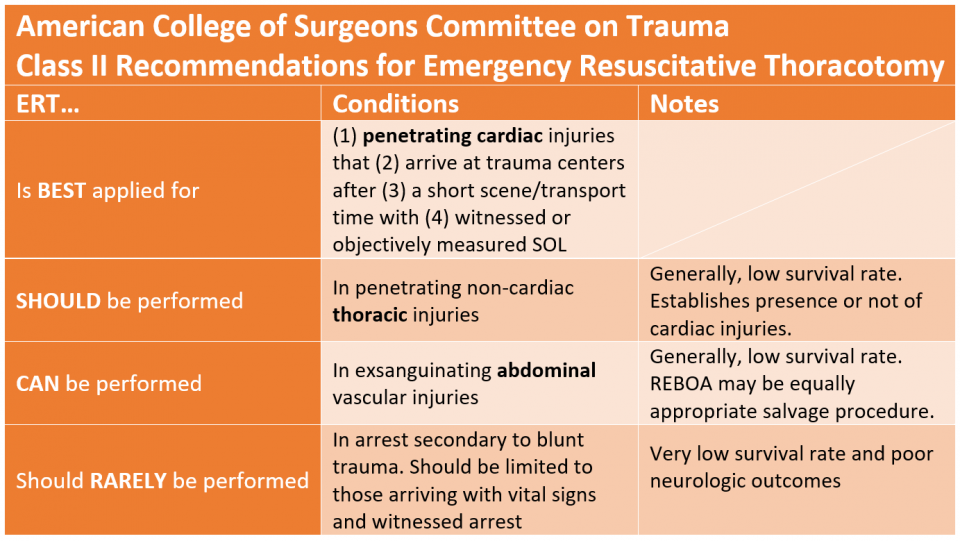

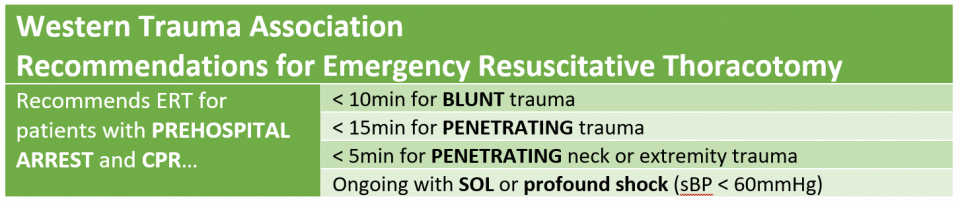

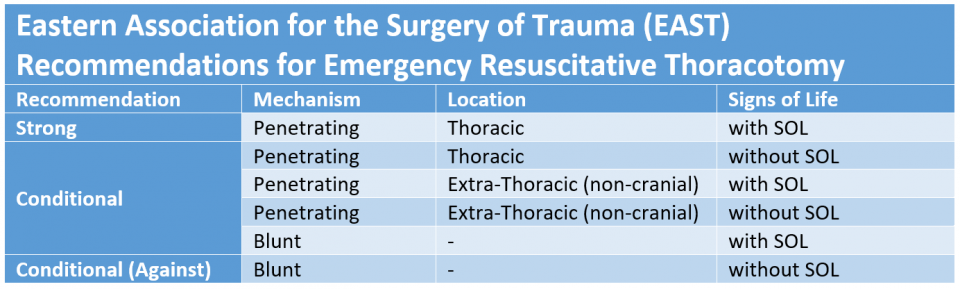

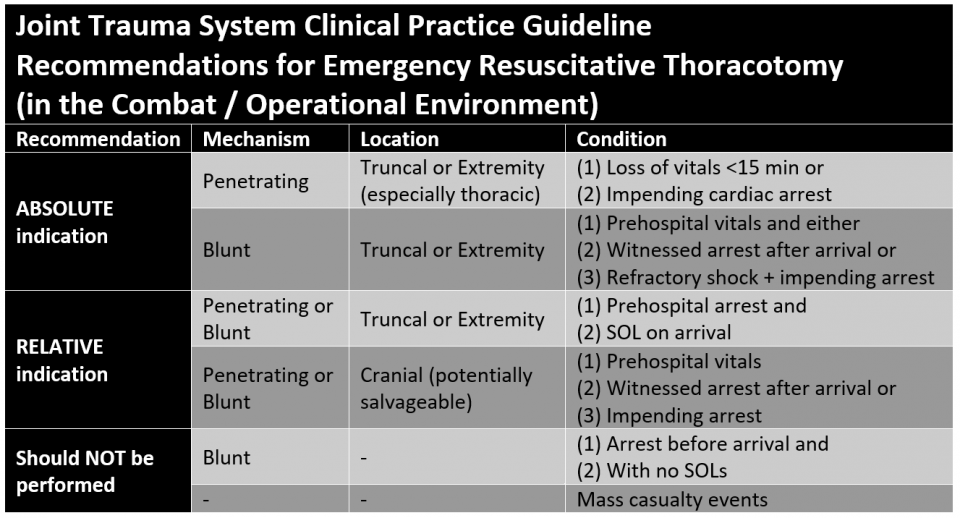

If you are wanting to learn more about how to start using POCUS, visit Practical POCUS. If you follow the link you can sign up for a free lung ultrasound course which includes topics around trauma but also COVID-19 related lung ultrasound. Tension Pneumothorax: A tension pneumothorax is classically taught as being managed with needle decompression. However, the placement has been changed from a mid-clavicular (anterior) approach to the fifth intercostal space slightly anterior to the mid-axillary line. Alternatively, finger thoracostomy can be effective and is essentially the first step to placing a chest tube. If a needle is used, it is preferred to be a 14 gauge needle that is 8 cm (3.15 inches) in length. Tension pneumothorax should be a clinical diagnosis as mentioned with ATLS and they recommend not delaying treatment for radiologic confirmation. Open Pneumothorax: An open pneumothorax is treated differently. Given that it requires a relatively small hole (2/3 the diameter of the trachea) for air to preferentially pass through the chest wall versus the trachea, it often requires immediate treatment. This is done by placing a three-sided occlusive dressing. The reason for leaving one side open is to "burp" the dressing as air can accumulate along the chest wall (like a more traditional pneumothorax). Massive Hemothorax: Massive hemothorax is defined as a 1.5 liter loss of blood or 1/3 blood volume output on chest tube. A third potential way to diagnose it is continued bleeding of 200 mL/hour for 2-4 hours. However, this means a delay with the third. The indication is for the patient to have an emergent thoracotomy when this occurs. Cardiac Tamponade: While cardiac tamponade is classically taught using Beck's Triad (hypotension, muffle heart sounds, and jugular venous distention [JVD]), but it is uncommon to even have one of the classic three criteria. Again, POCUS can be extremely beneficial to the diagnosis of a pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. It can help with the diagnosis very early and even facilitate the treatment including guiding the needle for pericardiocentesis. Traumatic Circulatory Arrest: The figure is above, but EMCrit has a superb podcast that dives into even more detail on how to manage the traumatic arrest. Just like every other topic, we cover this in the podcast in more detail. However, we cover how the ultimate decision becomes if we should perform a thoracotomy which is largely based on how the patient responds to the very initial measures, their mechanism, and the time since the onset of the traumatic circulatory arrest. This is a rather complex decision and a number of recommendations already exist from the American College or Surgeons, WEST, EAST, and Joint Trauma System (Military).

We have covered the life threatening injuries and complications that need to be identified as quickly as possible during the primary survey. Now, it is time to cover some of the findings that can occur during the secondary survey or can be at least partially delayed as they are not as time sensitive.

Simple Pneumothorax: While a pneumothorax can be observed that is smaller and/or asymptomatic, they may still require some treatment. This is especially true if they require positive pressure ventilation or will be transferred by air (helicopter or plane) due to the risk of the pneumothorax increasing in size with the change of pressure and leading to a tension pneumothorax. Hemothorax: A non-massive hemothorax is generally managed with a chest tube but not all will require more invasive surgery. Flail Chest and Pulmonary Contusion: While pulmonary contusions are a potentially lethal injury, these can take time to develop. These usually occur after multiple rib fractures such as a flail chest. Such patients need to be monitored and have supportive measures including sometimes needing oxygen and mechanical ventilation. Blunt Cardiac Injury: Troponins are not as helpful here but EKG and POCUS can be helpful. Again, these patients (like the others so far) require admission for continued observation. Traumatic Aortic Disruption: Chest X-rays are unreliable but a widened mediastinum may be seen. CTs are helpful especially with angiography. POCUS can be extremely helpful especially when these patients are unstable. Many of these patients will die before ever coming to the emergency department. However, those that make it to the emergency department should have their heart rate and blood pressure very well controlled. A short-acting beta block such as esmolol should be used with a target heart rate of less than 80 and a mean arterial pressure of 60-70 mmHg. Traumatic Diaphragmatic Injury: This is more commonly seen on the left side and can be seen in severe cases on chest X-ray but otherwise can be missed early if only using this as the imaging initially. Rarely, these can be missed by CT and require oral contrast to help visualized such an injury. Blunt Esophageal Rupture: This can present similar to Boerhaave syndrome and is usually from a penetrating injury. Other manifestations of chest injuries can be subcutaneous emphysema, crushing injuries to the chest, and fractures that include the include the ribs, sternum, and scapula. In general, children tend to have more flexible chest walls and are thus less likely to sustain rib fractures. When rib fractures are seen, this can be potentially concerning for non-accidental trauma. Scapular and sternal fractures usually require significant force and often require more extensive imaging if observed on chest X-ray initially. Note that an isolated scapular fracture is more likely to occur in young children. This wraps up another blog and podcast! There is plenty more trauma and ATLS coming in the near future! Let us know what you think by giving us feedback here in the comments section or contacting us on Twitter or Facebook. Remember to look us up on Libsyn and on Apple Podcasts. If you have any questions you can also comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

1 Comment

Ray

2/23/2021 04:16:30 am

Great job on the podcasts! It’s a great reference for my trauma rotation.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed