|

The newest Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) blog and podcast is here! This time we talk about head trauma. Get the key pearls and pitfalls as provided by Chip Lange and Mike Sharma.

Remember that the primary goal of treatment for patients with suspected traumatic brain injury (TBI) is to prevent secondary brain injury. This includes that computed tomography (CT) should not delay patient transfer to a trauma center that is capable of immediate and definitive neurosurgical intervention. This does not mean that CT should never be performed, but that obvious cases that need transfer should not be delayed by CT being performed at the initial facility.

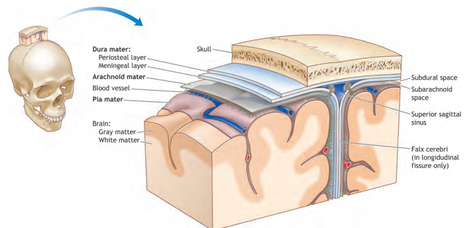

Brief Anatomy:

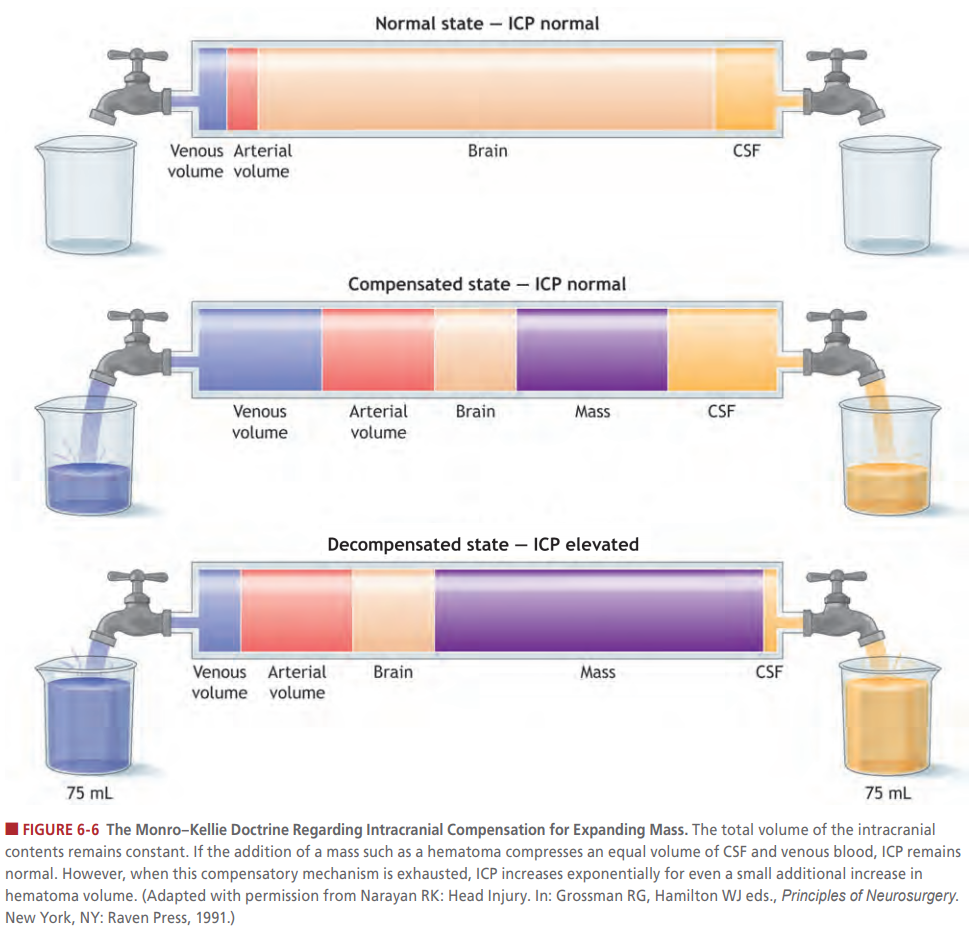

Brief Physiology:

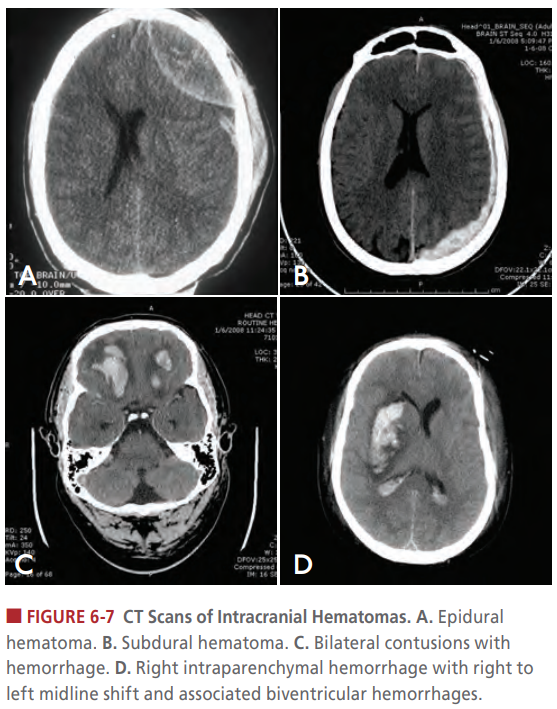

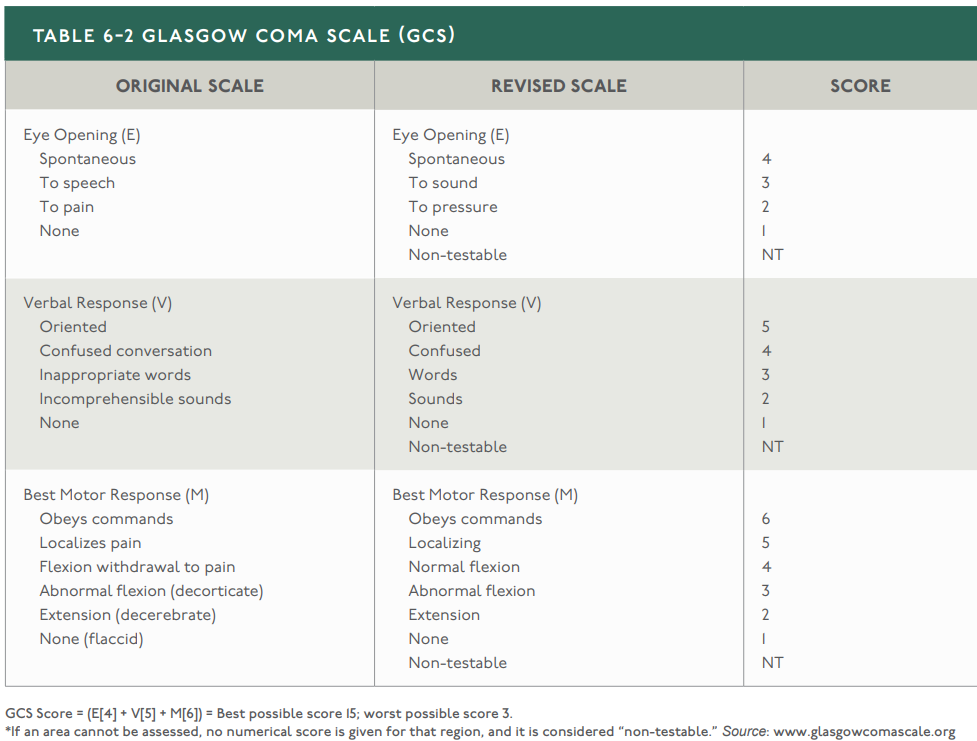

Head Injury Classification:

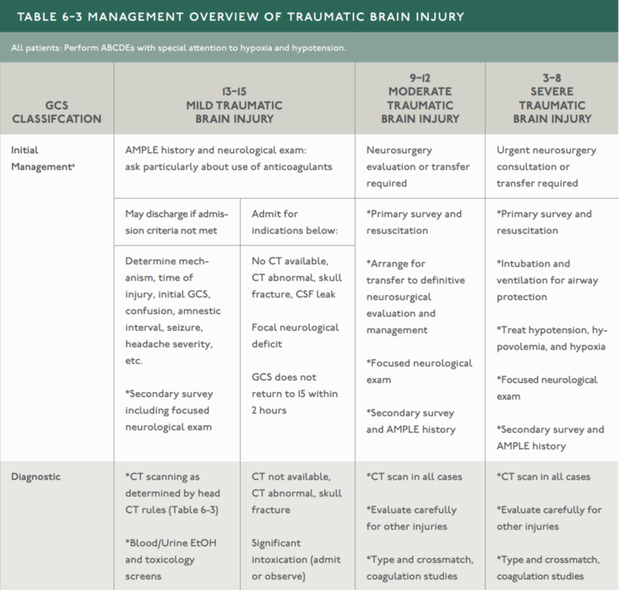

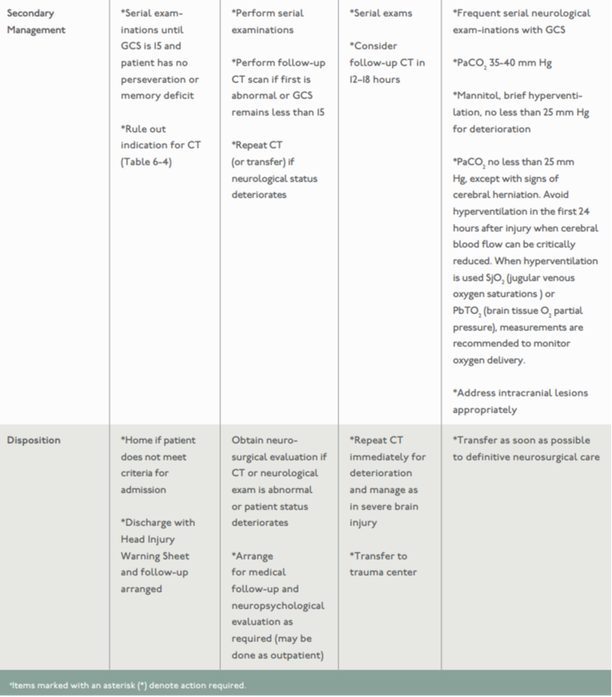

Treatment Guidelines:

Resuscitation:

Therapies:

Let us know what you think by giving us feedback here in the comments section or contacting us on Twitter or Facebook. Remember to look us up on Libsyn and on Apple Podcasts. If you have any questions you can also comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

12 Comments

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us. Radial head fracture treatment, Nursing diagnosis for head injury, Nursing management of head injury, head injury blood clot treatment, nursing management of head injury patient, medical management of head injury, surgical management of head injury, care of patient with head injury, forehead bump treatment, head injury surgery. <a href="https://curerehab.in/Head-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us. Radial head fracture treatment, Nursing diagnosis for head injury, Nursing management of head injury, head injury blood clot treatment, nursing management of head injury patient, medical management of head injury, surgical management of head injury, care of patient with head injury, forehead bump treatment, head injury surgery. <a href="https://curerehab.in/Head-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us. Radial head fracture treatment, Nursing diagnosis for head injury, Nursing management of head injury, head injury blood clot treatment, nursing management of head injury patient, medical management of head injury, surgical management of head injury, care of patient with head injury, forehead bump treatment, head injury surgery. <a href="https://curerehab.in/Head-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us. Radial head fracture treatment, Nursing diagnosis for head injury, Nursing management of head injury, head injury blood clot treatment, nursing management of head injury patient, medical management of head injury, surgical management of head injury, care of patient with head injury, forehead bump treatment, head injury surgery. <a href="https://curerehab.in/Head-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us. Radial head fracture treatment, Nursing diagnosis for head injury, Nursing management of head injury, head injury blood clot treatment, nursing management of head injury patient, medical management of head injury, surgical management of head injury, care of patient with head injury, forehead bump treatment, head injury surgery. <a href="https://curerehab.in/Head-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us. Radial head fracture treatment, Nursing diagnosis for head injury, Nursing management of head injury, head injury blood clot treatment, nursing management of head injury patient, medical management of head injury, surgical management of head injury, care of patient with head injury, forehead bump treatment, head injury surgery. <a href="https://curerehab.in/Head-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

4/3/2024 05:54:54 am

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us.Traumatic brain injury stroke recovery, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation, brain injury rehab, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation centers near me, brain injury rehabilitation near me, brain injury therapy, tbi physical therapy, traumatic brain injury clinic, traumatic brain injury care facilities, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation centers, traumatic brain injury rehab, brain injury treatment centers, rehab for brain injury near me, rehabilitation after brain injury<a href="https://curerehab.in/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

4/24/2024 06:16:41 am

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us.Traumatic brain injury stroke recovery, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation, brain injury rehab, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation centers near me, brain injury rehabilitation near me, brain injury therapy, tbi physical therapy, traumatic brain injury clinic, traumatic brain injury care facilities, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation centers, traumatic brain injury rehab, brain injury treatment centers, rehab for brain injury near me, rehabilitation after brain injury<a href="https://curerehab.in/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

4/25/2024 11:56:50 pm

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us.Traumatic brain injury stroke recovery, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation, brain injury rehab, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation centers near me, brain injury rehabilitation near me, brain injury therapy, tbi physical therapy, traumatic brain injury clinic, traumatic brain injury care facilities, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation centers, traumatic brain injury rehab, brain injury treatment centers, rehab for brain injury near me, rehabilitation after brain injury<a href="https://curerehab.in/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

5/10/2024 07:28:35 am

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us.Traumatic brain injury stroke recovery, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation, brain injury rehab, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation centers near me, brain injury rehabilitation near me, brain injury therapy, tbi physical therapy, traumatic brain injury clinic, traumatic brain injury care facilities, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation centers, traumatic brain injury rehab, brain injury treatment centers, rehab for brain injury near me, rehabilitation after brain injury<a href="https://curerehab.in/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

5/20/2024 05:39:11 am

This Blog Is Very Helpful And Informative For This Particular Topic. I Appreciate Your Effort That Has Been Taken To Write This Blog For Us.Traumatic brain injury stroke recovery, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation, brain injury rehab, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation centers near me, brain injury rehabilitation near me, brain injury therapy, tbi physical therapy, traumatic brain injury clinic, traumatic brain injury care facilities, traumatic brain injury rehabilitation centers, traumatic brain injury rehab, brain injury treatment centers, rehab for brain injury near me, rehabilitation after brain injury<a href="https://curerehab.in/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Rehabilitation"> physiotherapy in Hyderabad </a>

Reply

6/24/2024 12:44:10 am

Best Hair Bonding Services in Hyderabad

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed