|

Elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) was just discussed in our last podcast on head injuries. However, we briefly mentioned how there is a certain amount of controversy on this subject. This separate podcast is to act as a supplement to the Chapter 6 ATLS podcast on head trauma that was just covered. We find this particularly important given how long our ATLS podcasts run in general.

We should hit the basics first about these medications.

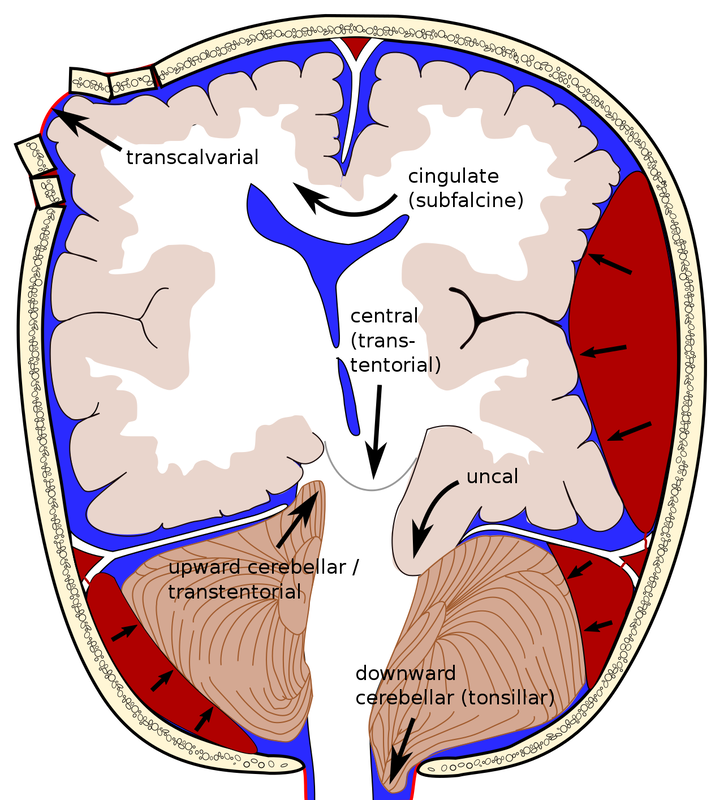

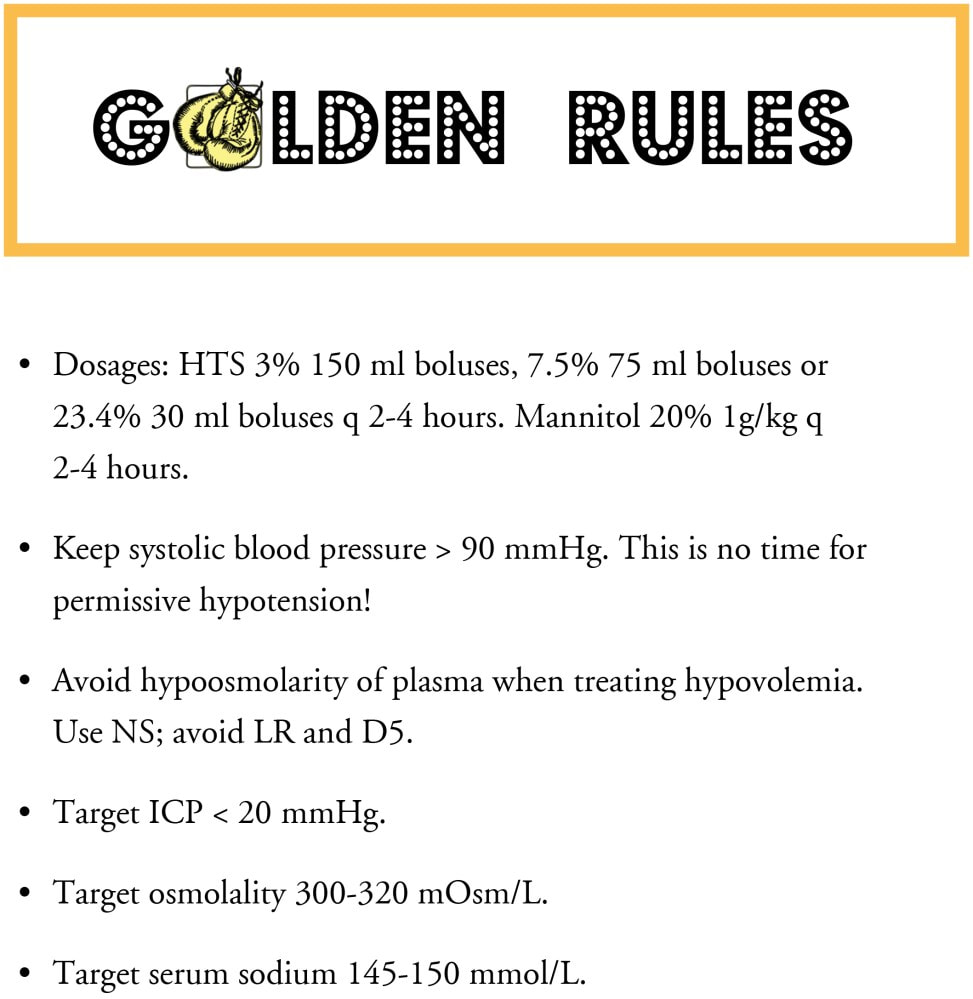

Mannitol (Osmitrol) is used to reduce ICP and is commonly prepared in a 20% solution (20 grams in 100 ml of solution). As ATLS and others would recommend, it should be avoided in hypotension because mannitol does not lower ICP in patients with hypovolemia and is a potent osmotic diuretic. The effect can further exacerbate hypotension and cerebral ischemia. Acute neurological deterioration (such as when a patient under observation develops a dilated pupil, has hemiparesis, or loses consciousness) is a strong indication for administering mannitol in a euvolemic patient. The recommended dosing is to bolus 1 g/kg rapidly (over 5 minutes) and to get them to definitive care (operating room if the lesion has been identified or to a CT scanner if it will not delay transport to a higher level of care). Mannitol should be avoided if the serum osmolar gap exceeds 18 mOsm/kg to 20 mOsm/kg. Some also suggest not exceeding a serum osmolality of 320 mOsm/kg if mannitol is to be considered. Hypertonic saline is also used to reduce elevated ICP. This is considered the preferable agent by many for patients with hypotension because it does not act as a diuretic. It is generally available in concentrations of 3% to 23.4% with a dosing limit based on an upper serum sodium limit of 155 mmol/L. Generally, the recommendation is to choose a small volume (to allow for more rapid infusion) of a higher concentration given over 15 minutes. Briefly, we should also mention that barbiturates are effective in reducing ICP refractory to other measures, although they should not be used in the presence of hypotension or hypovolemia. Furthermore, barbiturates often cause hypotension, so they are not indicated in the acute resuscitative phase. The hypotension can lead to the use of vasopressors. In turn, the increase in systemic vascular resistance caused by the use of vasopressors may lead to end organ hypoperfusion and significant metabolic acidosis which can in turn worsen the hypotension. This leads to a vicious cycle. The long half-life of most barbiturates prolongs the time for determining brain death, which is a consideration in patients with devastating and likely nonsurvivable injury. Barbiturates are not recommended to induce burst suppression measured by EEG to prevent the development of intracranial hypertension. Sometimes, a rapid bolus of IV pentobarbital is administered but drips are generally not recommended. ATLS states, "High dose barbiturate administration is recommended to control elevated ICP refractory to maximum standard medical and surgical treatment. Hemodynamic stability is essential before and during barbiturate therapy." We should also quickly explain brain herniation as it was only briefly discussed in the last podcast. The brain herniates when brain tissue is shifted from one space in the brain to another. This can occur side to side, down, under, or across rigid membranes such as the tentorium or falx. It can also occur through bony openings such as the foramen magnum or through openings from trauma or surgery. Below is a diagram demonstrated a variety of examples. Beside it are the "Golden Rules" as listed from another blog.

Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) can lead to increased ICP. This leads to poor cerebral perfusion and brainstem compression. The more we can reduce the ICP, the greater the odds of survival. Our goal should then focus on the rapid and effective control of ICP and avoidance of herniation.

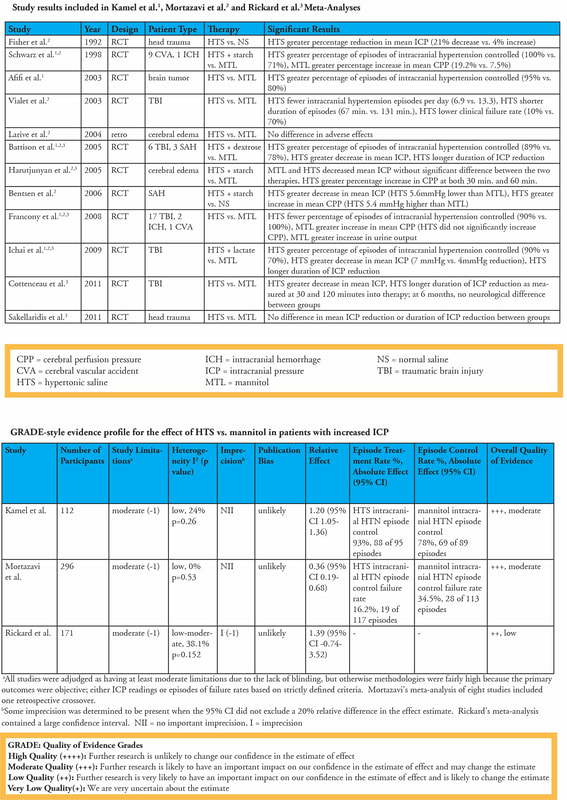

When we parse through the evidence, we can often look at meta-analyses. However, even when we look at data this way we still often have overall low to moderate evidence. A large part of this is due to these studies being small and heterogeneous. However, we should not fully discount these studies as there does appear to be some signal that higher quality studies will hopefully tease out in the near future. Given the overall rarity of right circumstances to perform randomized control trial (RCTs), it will be difficult to obtain a high quality study RCT with a large sample size, multicenter, and well controlled to answer the question of which is better. However, we should look at the evidence that does exist. The earliest study we will quote is from Critical Care Medicine published March 2011. This study found that hypertonic saline was more effective than mannitol for the treatment of increased ICP but admitted that there was a small number of eligible studies and they were also small in size. Surgical Neurology International published another article in 2015 focused on comparing the two in TBI specifically. Out of 45 articles identified, 7 were included in their review with 5 being prospective RCTs, one prospective non-RCT, and one a retrospective cohort study. There was heterogeneity in the studies on which was more efficacious but both hypertonic saline and mannitol did reduce ICP. Their conclusion was that it should be decided on a case by case basis given the number of factors that may be involved when deciding an appropriate agent. Cochrane in December 2019 also compared hypertonic saline to mannitol with acute TBI-related elevated ICP. They used 6 RCTs with 287 total patients. While they did try to compare hypertonic saline to a wide variety of agents, they only found studies comparing it to mannitol with or without glycerol. Their conclusions was that there was weak evidence that hypertonic saline was no better than mannitol in both efficacy and safety. Most recently, the Journal of Intensive Care published an article in August of 2020 on the effects of hypertonic saline versus mannitol in TBI patients in the prehospital, emergency department, and intensive care unit (ICU) settings. In this study, they looked at 4 RCTs with a total of 125 patients which all came from the ICU. With a low level of certainty, they found no significant difference in hypertonic saline versus mannitol in regards to all-cause mortality or in secondary outcomes. However, it can be beneficial to look at the individual small studies. Again, another blog has covered these studies quite well and is included below. When looking at the individual studies there does appear to be benefit of hypertonic saline over mannitol for the greater reduction of ICP including refractory elevated ICP, fewer failures, and better cerebral perfusion.

What does this mean in the end? Hypertonic saline has some potential signal for benefit over mannitol, but given the limitations of studies, their heterogeneity, and overall low quality of evidence when it comes to meta-analysis we still lack a clear, high quality answer. However, it does appear that hypertonic saline could be a better choice than mannitol and one worth considering in most cases.

Let us know what you think by giving us feedback here in the comments section or contacting us on Twitter or Facebook. Remember to look us up on Libsyn and on Apple Podcasts. If you have any questions you can also comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed