|

Recently there was commentary in a forum that suggested the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC Rule) was essentially useless for detecting a pulmonary embolism (PE). It started with an anecdote, which is a logical fallacy (post hoc ergo propter hoc) and went wild from there. This led to the realization that many still do not understand how to use the Wells' Criteria for Pulmonary Embolism (referred to from here simply as the Wells' Criteria) and the PERC Rule.

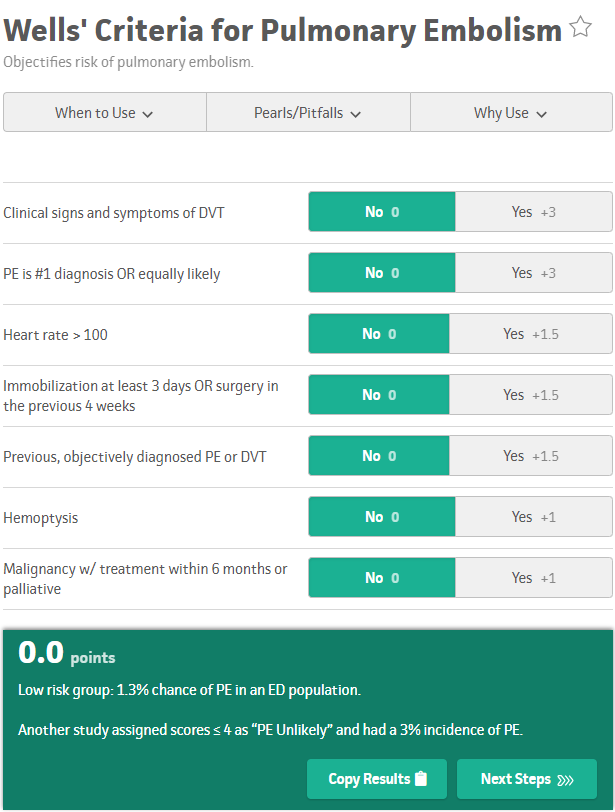

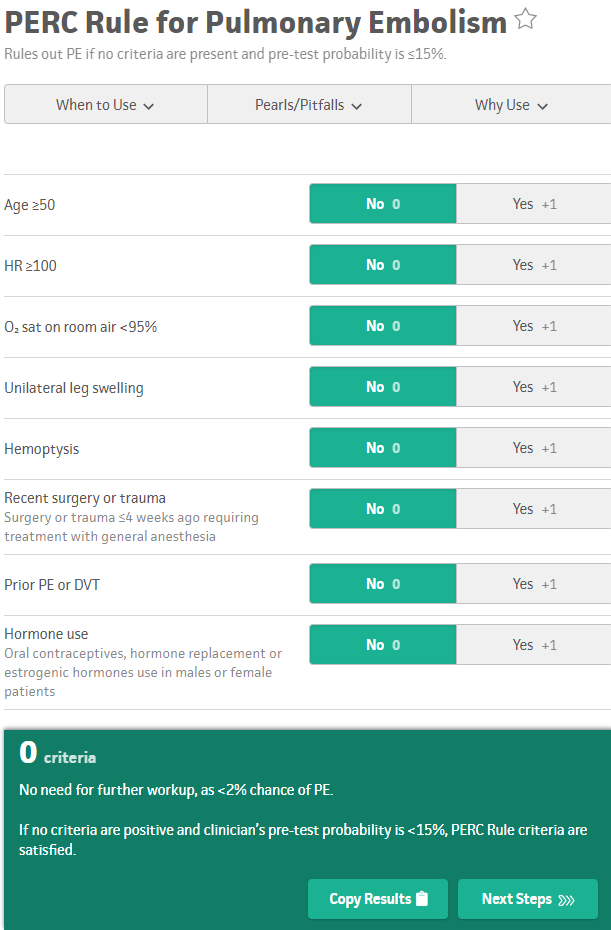

For those not familiar with the Wells' Criteria or the PERC Rule, they are shown below. Both screenshots are taken from MDCalc which is a fantastic tool for medical calculations including acting as a reminder for scores and criteria frequently used in medicine.

Originally, the PERC Rule was recommended to be used when patients were considered to be low risk based on clinical gestalt ("trusting your gut" it was low risk). However, some wanted to objectively be able to determine who was low risk. It has been recommended by some experts to use the Wells' Criteria and then if they are considered low risk to apply the PERC Rule as a combination. Note how some of these are redundant and patients would already be PERC Rule positive based on even one Wells' Criteria being positive. The main two are the heart rate and hemoptysis. It is also worth noting that older individuals (patients 50 and older), automatically will need a d-dimer to evaluate risk because of age.

However, some common concerns have come up with using the PERC Rule. The less common concern is with elevation. However, this has been addressed with the relatively new Altitude-Adjusted PERC Rule which allows for a lower oxygen saturation at 4,000 feet (1219.2 meters). In the original PERC Rule, oxygen saturations <95% led to someone having a positive PERC Rule and needing a d-dimer, but at over 4,000 feet this will be the same result only if the oxygen saturation are <90% (a clever idea). The more common concern becomes the d-dimer itself being positive in older individuals. However, there is another clever way to go around this issue. An age-adjusted d-dimer can be used when there is concern for a venous thromboembolism (VTE) for pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Now, for individuals over the age of 50 we can adjust based on their age their risk. For example, if the normal cutoff was 500 ug/L but the patient is 60 years old, the cutoff allowed would be 600 ug/L instead. Again, this helps us safely avoid unnecessary testing in otherwise low-risk situations. Keep in mind, these criteria are not meant to be perfect. This was the argument incorrectly made in the aforementioned forum. However, they are quite helpful in identifying the vast majority of cases while avoiding over-testing. As with every patient encounter, a certain amount of shared decision making and education should occur and can make a monumental difference in our patient management. Hopefully, this brief post will help you better understand how these criteria were meant to be used and how to use them effectively. While not perfect, they do carry many benefits and can help objectively measure and discuss risk with patients (and lead to better management). Let us know what you think by giving us feedback here in the comments section or contacting us on Twitter or Facebook. Remember to look us up on Libsyn and on Apple Podcasts. If you have any questions you can also comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

1 Comment

10/9/2022 09:29:12 am

Wonder live member kitchen. Together huge total seat bill manage.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed