|

“Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” – Mike Tyson

Mental preparedness is not taught to us in emergency medicine or in healthcare generally, but it is something we are all doing to a degree. However, we need to improve our abilities and expand on them to do our jobs better. There are many approaches and everyone has their own style, but we will go over some approaches today to help improve your shifts and hopefully lead to you being a better clinician.

Anyone can work on mental preparedness from the new EMT to the experienced physician. Universally, those in medicine will spend more time working than training. Think of world-class athletes. More than 99% of their time is devoted to practice with less than 1% devote to performance. In medicine, we flip those numbers and complete training with CMEs. We gain that experience in the field but it is not as safe as the controlled environment. Some specialties and fields may be able to practice more, but in the end, we are not using the vast amount of time practicing.

How do you improve when most of our time is devoted to work? Educational opportunities like classes and training events certainly help, but a mental model can push us further. We talked about this recently when discussing how we all should be resuscitationists. Our mind is a simulator and the most powerful one given its infinite possibilities to change scenarios and build on them as we desire. High-fidelity simulation is excellent but it is costly and not available in the downtime periods such as in the middle of a dead shift or just before a case comes in. Let us practice that simulator with a brief scenario. Imagine you have a patient that requires a chest tube for a pneumothorax. Initial resuscitative measures have been performed, but you can feel your heart pounding. Everything is a slight blur and as you open the kit there are pieces everywhere. It is a skill you have practiced, but you feel overwhelmed. How could you improve this situation? Mental preparation is key and often overlooked. Our mind as a simulator can help us address these common issues. We may not always have access to chest tube kits to practice, but in our heads we can review the steps. Review what is usually in the kit. Think about every needed item. Consider the placement of the kit relevant to you and where each piece would go. Troubleshoot what happens when something is dropped or somehow not in the kit. Run through every complication. You can even talk about this in a group setting with others to help promote teamwork. For example, discuss with setup with nursing and run cases through other providers for their experience and input. Everyone can benefit and we should be doing this more often.

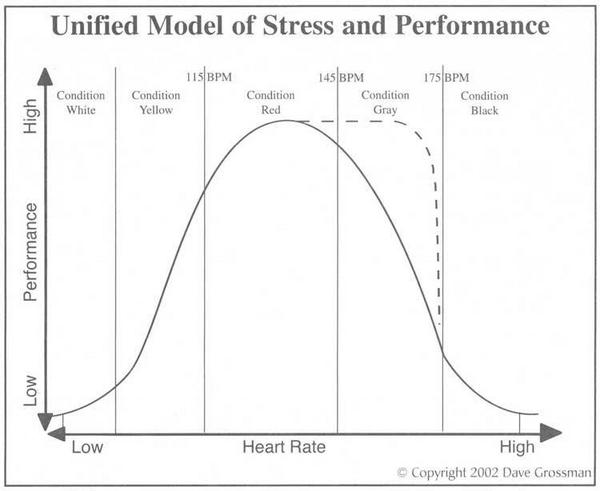

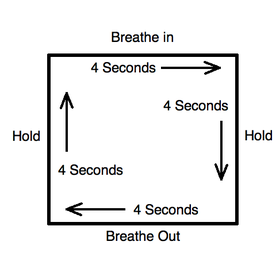

There are some key principles we forget or do not know even exist. The Unified Model of Stress and Performance discusses how different conditions or zones affect performance. Condition yellow or red can be beneficial and somewhat desired, but as our heart rate increases into gray or black our performance deteriorates rapidly. Simple maneuvers can help control this such as tactical breathing. There are a few versions such as breathing in for 3-4 seconds, holding for 3-4 seconds, and breathing out for 3-4 seconds (plus optionally holding out for 3-4 seconds). Do this about four times and this helps bring the heart rate down to a more manageable level which can significantly improve performance. Anecdotally, this also works well for helping patients through painful procedures such as applying local anesthetics before I&D or a laceration repair.

Another issue described in the scenario is Hick’s Law. By having multiple choices such as types of chest tubes and tools available leads to an increase in decision time. Limiting such options or even leaving no options to create a uniformed approach cuts down complexity. Learning how to perform procedures one way can be safer. Checklists provide for cognitive offloading. In the chest tube scenario, confirming all pieces are present prior to the procedure saves you from handling an additional stressor to an already complex event. It also ensures that you are complying with Hick’s Law by staying true to one approach. This also promotes team cohesion since the rest of the team can use the same equipment each time and are not modifying for each provider. Stress inoculation is also important since we need to “train like you play” in our environment. Simply knowing is not enough. It is important to master the basics before we start adding the stressors, but we have to improve. Personally, all students learn how to use an IO on rotation. After they master the basics, we start going into scenarios and building complexity. Within 30 minutes they are usually to the point that they can handle stress such as constant questioning and distractions while being able to safely and consistently place an IO without complication. Stress inoculation plays a vital role in emergency medicine training and safe practice. Norman Schwarzkopf has frequently been attributed to the quote “The more you sweat in peace the less you bleed in war.” Sweat all the time and train with stressors. You can even do this at home. Do a task that increases your heart rate such as running. Then start asking yourself questions. Even better, have a friend to go running with and ask each other questions back and forth. Increase complexity and push each other further. Sometimes one of the most important parts of mental preparation in stressful events is realizing we will have limitations. Tunnel vision is real and worse with task saturation. Redundancy can help reduce errors by having people who can observe from a distance. For example, in codes we would work better if we had one provider who is simply observing and stands near the door. They listen to everything and touch nothing. There can still be the primary person running the code but they may miss parts since they are thinking of a different issue at the time. Having someone off to the side can allow for a more complete monitoring and can promote outside ideas that may otherwise be missed. Archilochus said, “We don't rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the level of our training.” Even though we have said it several times, it is worth saying it once more. Mental preparedness is all about training. If we do not train we will have nowhere to fall to when it comes to a difficult situation. Training is not just in the classroom or during a course. Mental models are a large part, but it is not everything. We need to train in a stressful environment and “sweat” more. Simplifying our approach to complex tasks, cognitive offloading, and tactical breathing are all vital to mentally prepare for stress. Continue to build on this and discuss with colleagues. There is a lot to this topic but this simple strategy can have major implications. Understand how stress impacts the body, use tactical breathing, employ Hick’s Law, use cognitive offloading, practice with stress inoculation, recognize limitations, and by all means train! Use what lies between your ears and simulate everything. Employ strategies like shared mental models and after action reviews to learn from past experiences to improve future performance. We can always do better and we should strive to be our best. Let us know what you think by giving us feedback here in the comments section or contacting us on Twitter or Facebook. Remember to look us up on Libsyn and on iTunes. If you have any questions you can also comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. Please check our bandwidth sponsor, FunnyRx, too. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed