|

We return with our second podcast featuring EB Medicine content. Our partnership with them allows us to access their content and share it with you through the power of #FOAMed and this time we are tackling an all too common emergency: appendicitis. Specifically, we discuss the pediatric population given their most recent evidence-based review article on the same.

For free access to this article make sure to click this link. If you do not have a subscription yet with EB Medicine you will not be able to get the associated CME. However, check out the end of our show notes to learn how you can get access and at a great discount.

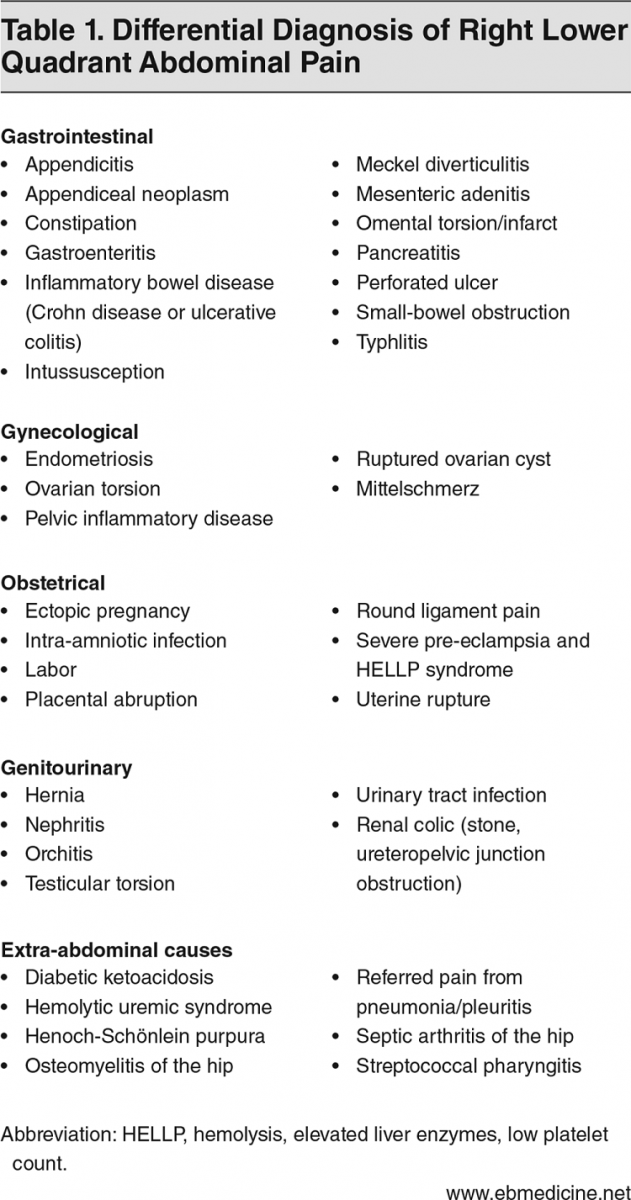

Many of the patients we see in acute care settings complain of abdominal pain. Often, especially at this time of year, it can be associated with vague symptoms. There may have been a fever, some nausea and/or vomiting, along with some URI symptoms. In children, this can be even more challenging to discern if this is a secondary symptom or the main problem. As we start to evaluate the patient and talk with their caregivers the story of right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain is mentioned. Does this mean it is appendicitis? There are a variety of potential causes but we included a list of differential diagnoses to consider below.

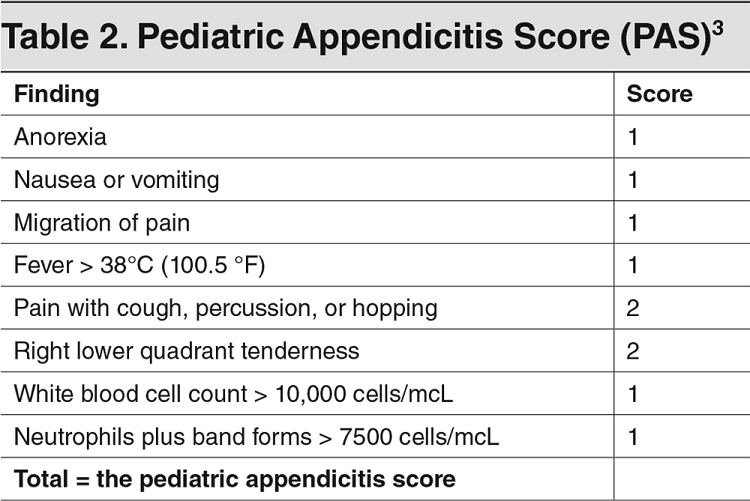

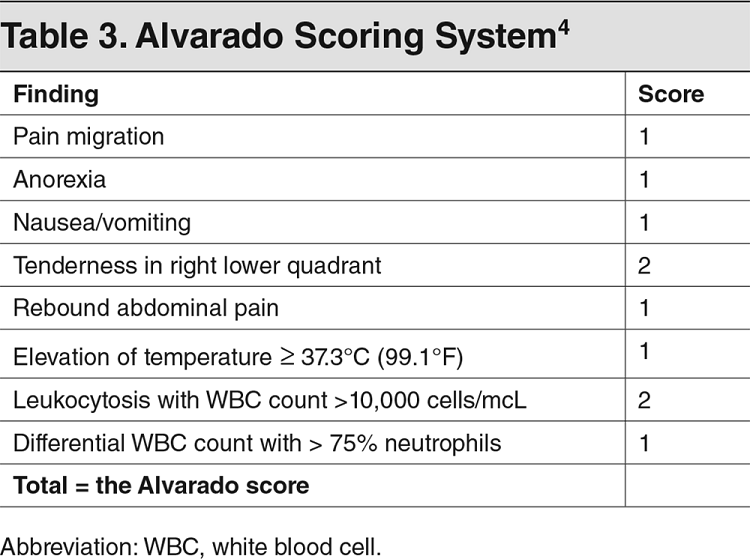

Keeping a broad differential in mind when someone mentions RLQ pain, now we need to move on to the history and physical. There are many teachings with evaluating appendicitis, but how accurate are these different assessments? The honest answer is that no single finding is enough. There are some scoring systems which can assist our decision making. Two of the most common, the Pediatric Appendicitis Score (PAS) and the Alvarado Scoring System, are shown above and can also be found at sites like MDCalc. There are even newer systems such as the Pediatric Appendicitis Risk Calculator (pARC) but it is worth noting that all of them require labs.

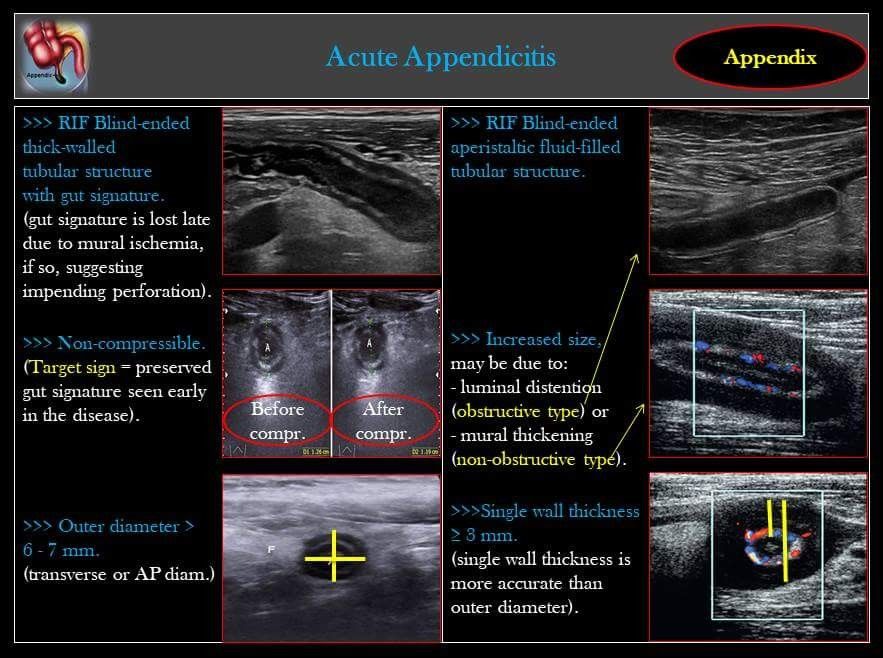

There are mainstays that we see across scoring systems that we should focus on: anorexia, nausea and/or vomiting, pain to the RLQ, this pain usually having migrated over time, pain with certain activities (walking, coughing, hopping, percussion, etc), and an evaluation of the CBC including a neutrophil count. A history and physical have been performed and you order labs including a CBC, metabolic panel, CRP (optional), pregnancy test for any female of potential child bearing age, and urinalysis. What else can you do to care for this patient? They should have nothing by mouth (NPO), receive IV hydration as needed, antiemetics such as IV ondansetron (0.15 mg/kg/dose up to 8 mg every 8 hours), and pain control. Despite the dogma, their is evidence both in RCT and meta-analysis form to support treatment without impeding the diagnosis. Now that the labs are returning, you can use the scoring method of your choice and follow the appropriate recommendations. Often, this is not a slam dunk case. Many times, imaging is recommended. In most cases this means ultrasound given its benefits in evaluation without radiation. We recently covered the use of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) in appendicitis on Podcast #161. As a quick reminder, below are the common findings.

If you have not yet had the training to perform POCUS (such as through a Practical POCUS course), you may have missed the chance to diagnose the patient earlier in their visit. However, there is still time to obtain the appropriate imaging through the radiology department. Unfortunately, ultrasound may not always be able to identify the appendix or fully assess due to a variety of issues such as body habitus or bowel gas. This is when it becomes more challenging to decide on the next step. At that point, there are several options. In lower risk scenarios, the possibility of admission for observation can be considered. A CT or MRI is another potential option. However, CT does expose a young patient to radiation which can increase their lifetime risk of cancer. MRI can be used but it is not universally available, takes the longest to perform, and may require the patient to be sedated (which has its own risks).

The needed imaging has been performed and the algorithm followed. The disposition is vital. If a patient of low risk is to go home, outpatient evaluation or repeat follow up in the department is necessary as the situation can change. Patients to be admitted for observation may do so under surgery or pediatrics depending on local policy and situation. If the diagnosis of appendicitis is made, discuss with the surgeon the findings and confirm a plan. In most cases, patients are still undergoing surgery but there has been newer evidence for nonoperative management. The surgeon will most likely recommend antibiotics to be started prior to surgery. These IV antibiotics may vary based on allergies and findings but are most often ceftriaxone 50-75 mg/kg/day (up to 2000 mg) as a single dose plus metronidazole 10 mg/kg/dose (up to 500 mg a dose) every 8 hours. Did you enjoy the content? Would you like to learn more about EB Medicine? Right now, you can get $50 OR MORE off a subscription with EB Medicine. Just click on this link and go to their website. Let us know what you think by giving us feedback here in the comments section or contacting us on Twitter or Facebook. Remember to look us up on Libsyn and on iTunes. If you have any questions you can also comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed