|

Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening condition that requires early recognition and appropriate treatment for the best outcomes. In pediatric cases, this can be more challenging for a variety of reasons including the barriers to obtaining a history and physical, knowing the appropriate dosing of medications, and the general stress of managing sick pediatric patients. We discuss how to manage such patients in this EB Medicine special.

For free access to this article make sure to click this link. If you do not have a subscription yet with EB Medicine you will not be able to get the associated CME. However, check out the end of our show notes to learn how you can get access and at a great discount.

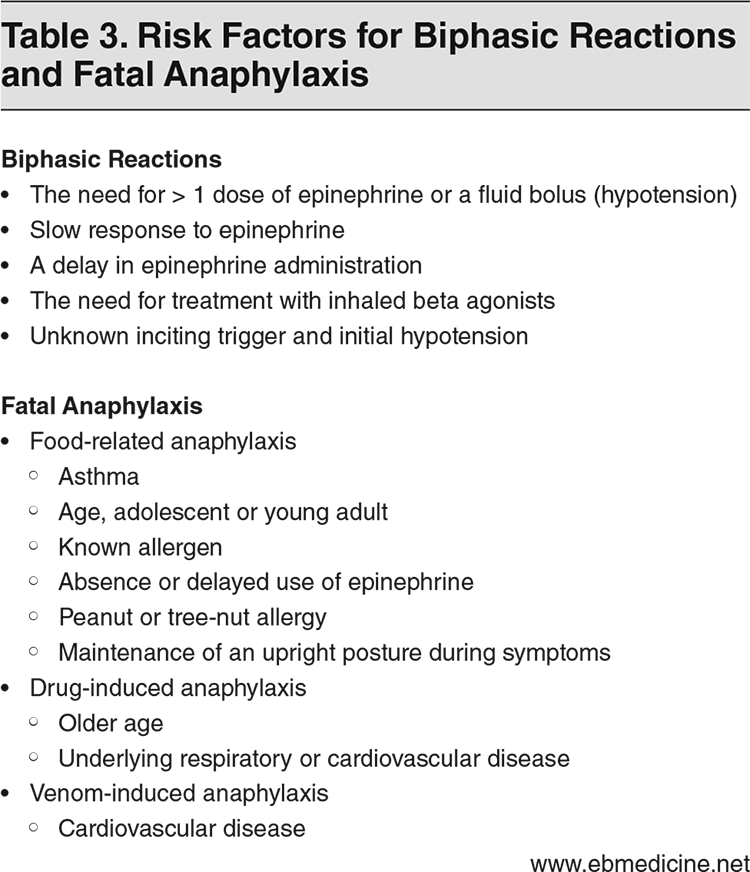

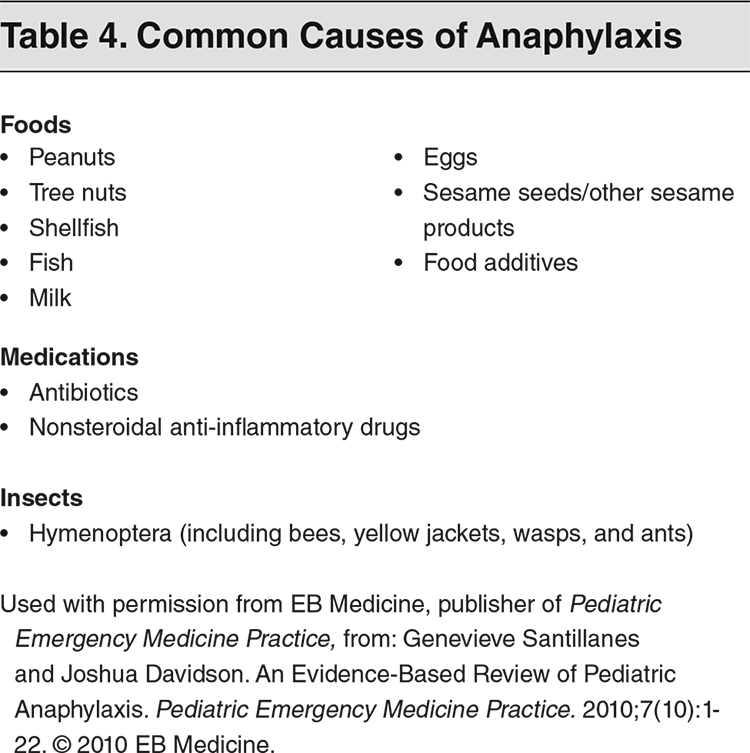

It has been almost three years since the last time we discussed anaphylaxis (Podcast #19). For that reason, we wanted to provide and update. As mentioned, EB Medicine published a great discussion regarding anaphylaxis specifically in pediatric patients. One of the key aspects to identifying anaphylaxis is to understand the diagnostic criteria. In all, there are many ways to define anaphylaxis but there are three main criteria: 1. The acute onset of a reaction within minutes or hours involving skin and/or mucosa paired with either respiratory compromise or cardiovascular collapse. 2. Use the second criteria set for symptom development from exposure to a likely allergen. Any of the following two categories are needed for diagnosis: involvement of skin and/or mucosa, respiratory compromise, cardiovascular collapse, or gastrointestinal symptoms. 3. If a patient has a reduced blood pressure after exposure to a known allergy within minutes or hours, this meets the third criterion. Hypotension is usually defined as a systolic pressure of less than 90 mm/Hg or a 30% decrease from baseline. In children, blood pressure for those less than 10 years old is defined differently. At less than a year old it is a blood pressure of 70 mm/Hg. Between years 1 and 10, it is 70 with the age times two. A quick example would be that for a 5 year old child, the systolic pressure concerning for hypotension would be 80 mm/Hg. We will talk more about treatment after we identify this condition, but we should first ask about what the common causes of anaphylaxis. Additionally, we need to know the risk factors for biphasic reactions and more importantly fatal anaphylaxis. The two tables below from the EB Medicine publication display this in an easy to understand format. True biphasic reactions are uncommon but are often considered to be a recurrence of symptoms within 72 hours without re-exposure to the trigger. Although common causes of anaphylaxis are from foods, medications, and insects the exact trigger can sometimes be difficult to identify. Thus, some biphasic reactions may actually be from a second exposure. With limited evidence, those who have complete resolution of their symptoms within 30 minutes of treatment did not have a biphasic reaction. Given the overall low incidence and the prolonged period after a reaction can occur, it can be challenging to know what patients may require admission. However, evidence has demonstrated that it is a low enough risk that prolonged routine monitoring of patients whose symptoms have resolved is likely unnecessary for patient safety. The main concern becomes those who are at risk for fatal anaphylaxis. This is calculated to be 1 death per million people per year. Pediatric patients who have anaphylaxis have a <1% mortality rate. Elderly patients do have an increased risk for fatal anaphylaxis in the United States and is more commonly from medications (59%) than food (7%). Another interesting finding from the literature reviewed by EB Medicine is that <15% of patients who had fatal anaphylaxis had cutaneous symptoms. This may be from the lack of recognition of anaphylaxis since it has less of the "classic" presentation. A good history and physical asking about potential triggers and symptoms can help more readily identify anaphylaxis and possible causes. Asking about comorbidities can help identify risk factors for biphasic reactions or fatal anaphylaxis. The physical exam may not always be impressive. Wheezing, edema, and urticaria are all classic findings but may not be present. Vital signs are another important part especially when checking for hypotension. Remember to factor in the normal heart rates and blood pressures for a pediatric patient when looking at this diagnostic criteria.

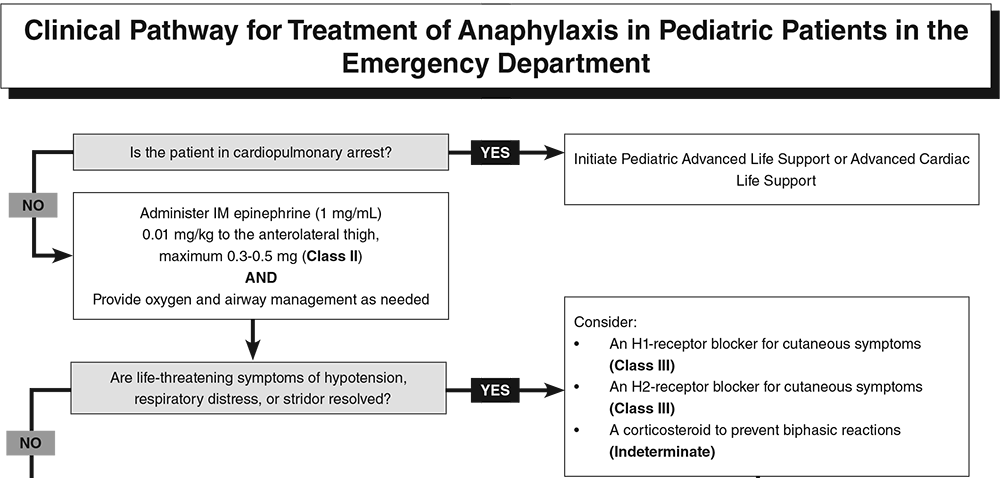

Early recognition is the key to providing high quality care. In the prehospital setting, this is especially easy to miss given the wide variety of signs and symptoms paired with an often chaotic environment. However, it is this early recognition that can improve patient outcomes and avoid death. Epinephrine is the first-line agent and should be given as early as possible. Intramuscular (IM) is the primary method of delivery both those in anaphylactic shock may require intravenous (IV) dosing. Early administration of epinephrine has been linked to an increased rate of survival.

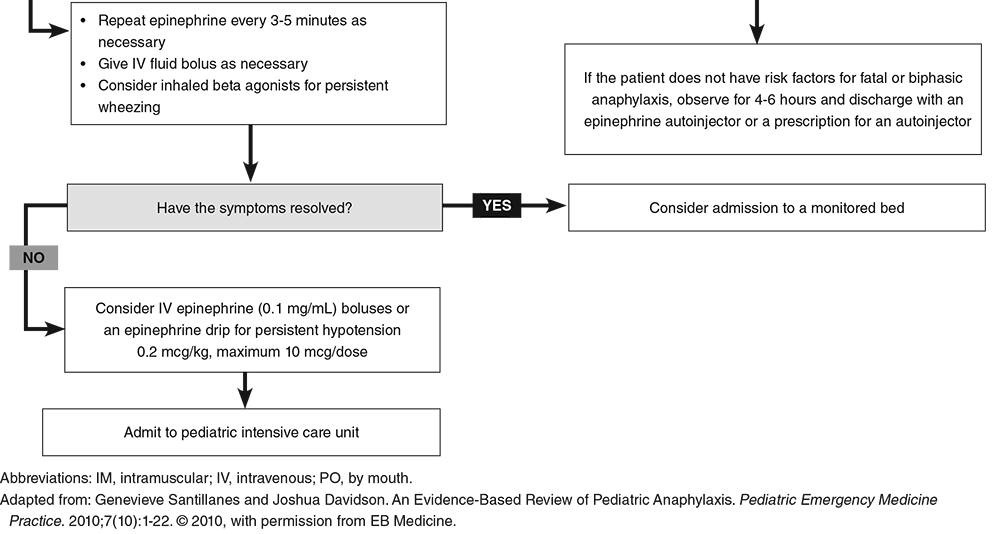

The dosing of epinephrine is 0.01 mg/kg of the 1 mg/mL concentration up to 0.5 mg. IM dosing is more rapid to receive peak plasma concentrations compared to subcutaneous (SQ) delivery. If given IV, the bolus dosing is 0.2 mcg/kg to a maximum of 10 mcg for persistent hypotension based on the Second Symposium on the Definition and Management of Anaphylaxis. However, The Resuscitation Council (in the UK) has guideliens of 1 mcg/kg of 0.1 mg/mL to a maximum of 50 mcg IV. For IV infusion, the Resuscitation Crisis Manual (RCM) recommends 1-20 mcg/min. The dosing is variable but the key is to give the medication as early as possible. Airway management is also at the top of the pathway for treatment. Supplemental oxygen may be needed and breathing treatments including the use of albuterol may be indicated. This is especially true if wheezing is present. For significant edema, especially if worsening despite appropriate treatment, occurs early intubation may be needed. It is vital to remember that a surgical airway may be necessary given the significant amount of edema that can rapidly occur.

The immediate life-threats have been address via a combination of Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) as applicable along with timely dosing of epinephrine. The airway has been managed, oxygen has been provided if needed, and any respiratory distress or stridor is under control. It is worth mentioning that adjunctive medications could be used. Antihistamines may help especially with cutaneous symptoms and can include both H1- and H2-receptor blockers. Additionally, a corticosteroid can be beneficial in helping control symptoms as well as reducing the risk for biphasic reactions.

Now that we have discussed evaluation and management, disposition is the final step. Monitoring can vary greatly by setting and recommendations. These patients should be symptom free at discharge and in most cases this will occur very quickly after treatment. It is important in patients that are discharged that they have the appropriate outpatient management. This includes home use of an epinephrine autoinjector for emergencies and further evaluation by their primary care and/or an allergist. Those patients needing to stay in the hospital for further management will go to an intensive care unit. Did you enjoy the content? Would you like to learn more about EB Medicine? Right now, you can get $50 OR MORE off a subscription with EB Medicine. Just click on this link and go to their website. Let us know what you think by giving us feedback here in the comments section or contacting us on Twitter or Facebook. Remember to look us up on Libsyn and on iTunes. If you have any questions you can also comment below, email at [email protected], or send a message from the page. We hope to talk to everyone again soon. Until then, continue to provide total care everywhere.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Libsyn and iTunesWe are now on Libsyn and iTunes for your listening pleasure! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed